Memory: Natural and Artificial

Created by Yuwei SunAll posts

This post provides a literature review on natural memory to bolster our recent study on the Associative Transformer. This architecture features two complementary memory systems: one built on attention-based explicit memory and the other on Hopfield memory.

Complementary Learning Systems Theory [1] [2]

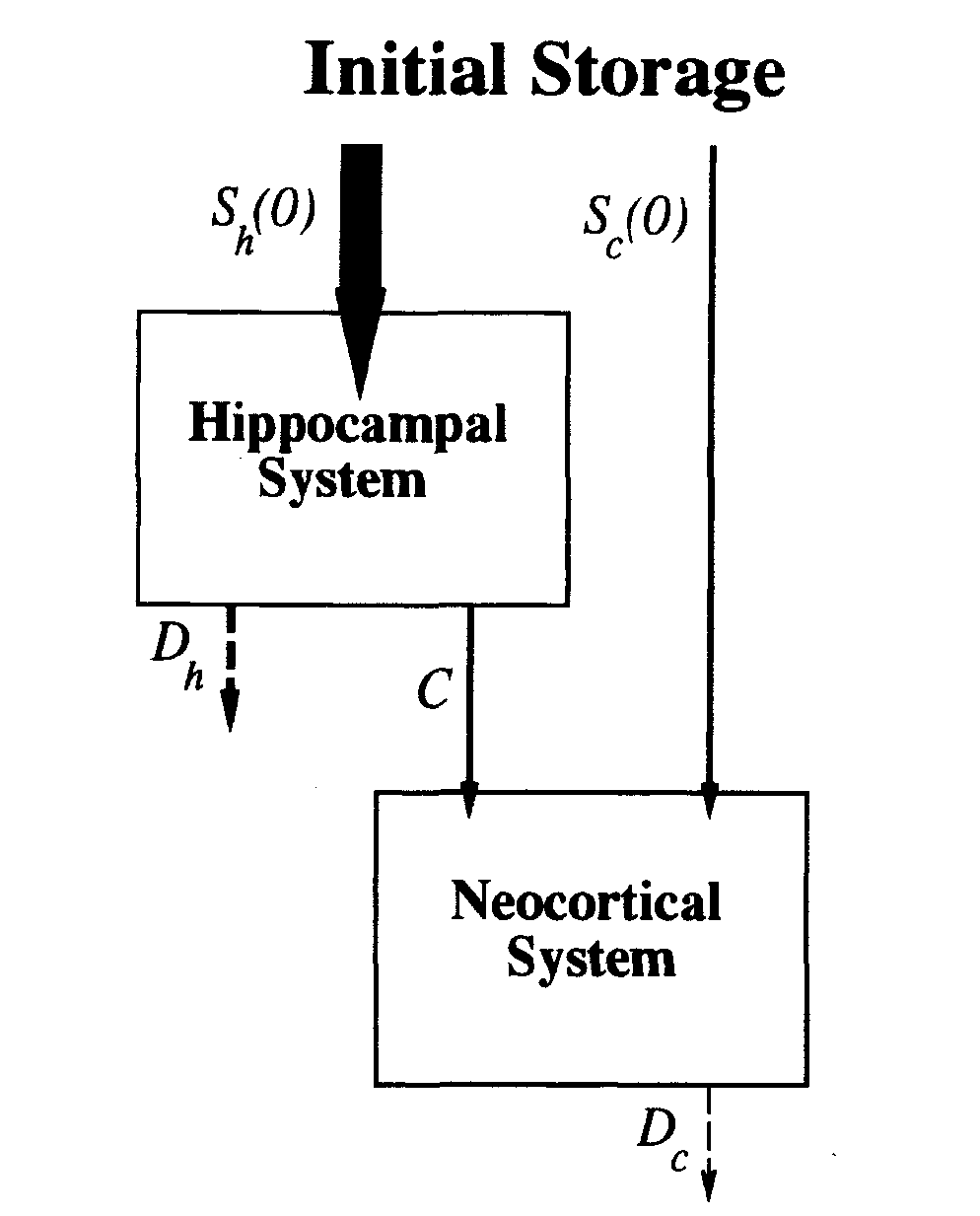

Complementary Learning Systems (CLS) theory postulates that intelligent agents require two learning systems, which are instantiated in mammals through the neocortex and the hippocampus. The neocortex gradually acquires structured knowledge representations, while the hippocampus quickly learns the specifics of individual experiences (Figure 1). One might wonder why a hippocampal system is necessary when memory task performance ultimately relies on changes in neocortical connections. The answer lies in the hippocampus serving as an intermediary for the initial storage of memories in a format that does not disrupt existing neocortical knowledge. This concept draws parallels between working memory (which deals with recent, relevant information) and reference memory (concerned with invariant aspects of task situations) and the CLS theory.

Hippocampal storage

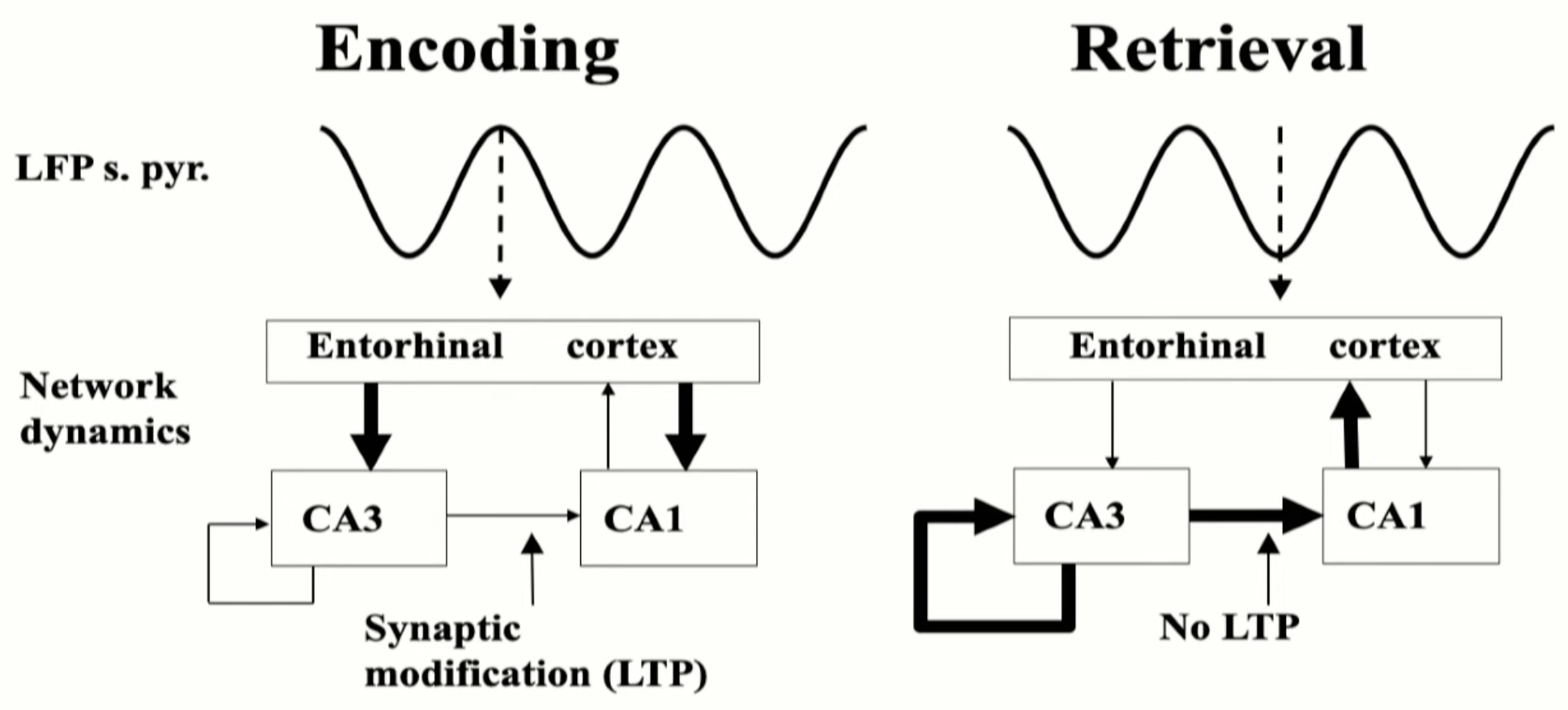

Within-system consolidation refers to the stabilization of recently formed memories within the hippocampus, possibly involving the strengthening of synapses among hippocampal neurons. The neocortical representation is thought to be condensed into a smaller set of neurons within the hippocampal system. The entorhinal cortex serves as the final convergence point for neocortical inputs to the hippocampus. Central to the hippocampus's role in storing specific experiences are two complementary computations: pattern separation and pattern completion. The Dentate Gyrus (DG) subregion of the hippocampus accomplishes pattern separation by orthogonalizing incoming inputs before their auto-associative storage in the CA3 region. Additionally, the CA3 subregion plays a crucial role in pattern completion, allowing for the retrieval of an entire stored pattern, equivalent to an entire episodic memory, from partial input, consistent with its function as an attractor network. Prediction is suggested as a role for the hippocampus in foreseeing the future based on the present and recent past. This can result from associative storage and retrieval through pattern completion. Processing of both spatial (e.g., place) and non-spatial (e.g., what happened) aspects of an event is believed to occur primarily in parallel streams before converging in the hippocampus at the DG/CA3 subregions.

Hippocampal replay

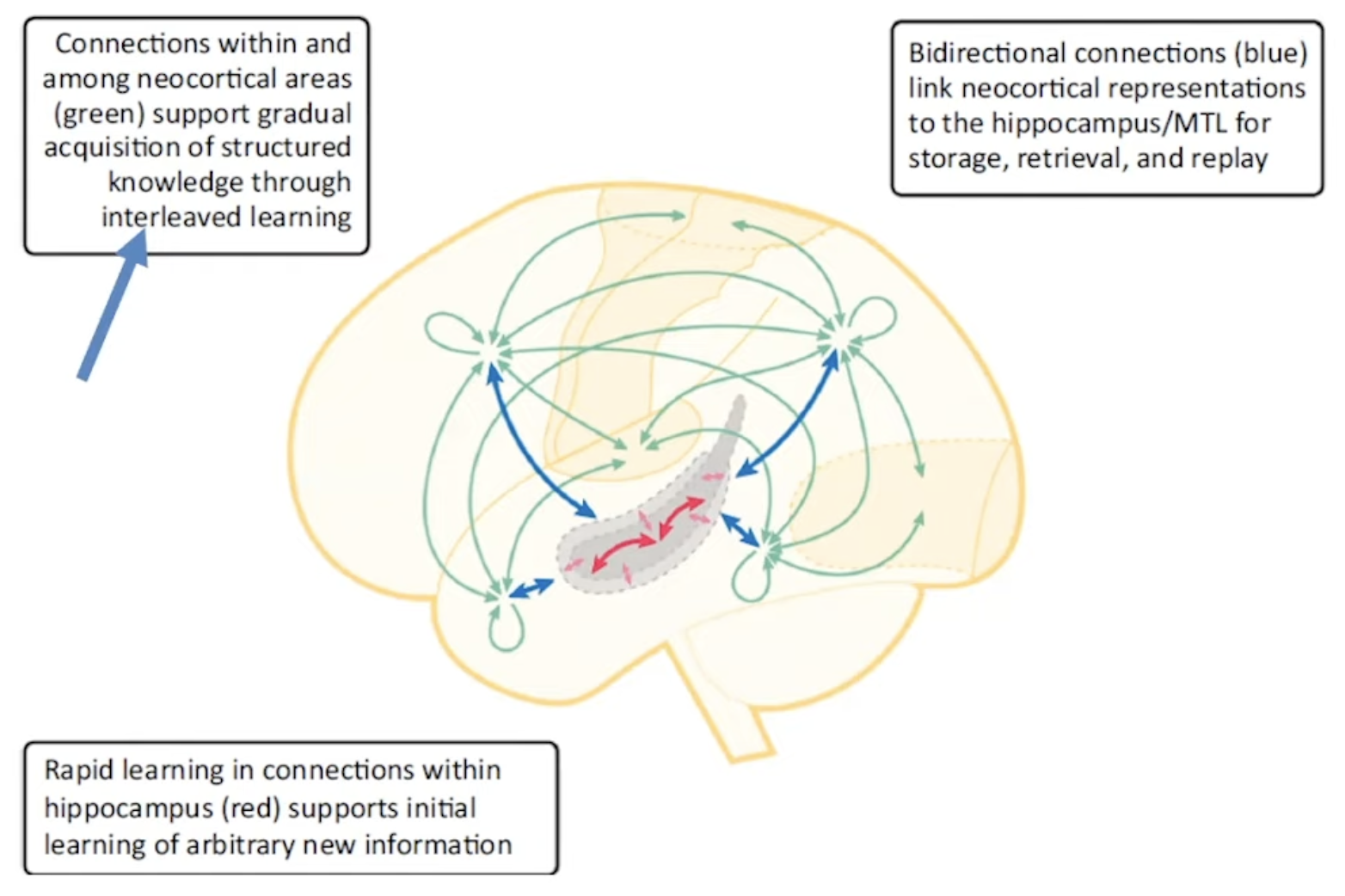

Systems-level consolidation pertains to the gradual integration of knowledge into neocortical circuits (Figure 2). Replay of recent experiences occurs during periods of rest or offline states, such as during sleep. During replay, the hippocampus and neocortex collaborate to facilitate interleaved learning (Figure 3). The DG plays a critical role in this process by selecting distinct neural activity patterns in CA3 for each individual experience. This mechanism provides an opportunity for gradual adjustments in neocortical connections, allowing memories initially reliant on the hippocampal system to gradually become independent. In this sense, the hippocampal memory system acts as a teacher for the neocortical processing system. The knowledge that underlies neocortical processing capabilities is believed to be encoded within these connections. Concepts like semantic memory and category learning can emerge through the gradual accumulation of small changes stemming from individual events and experiences. Infantile amnesia, the absence of explicit memories from early life, may be attributed to immature hippocampal traces that are challenging to access and interpret as the neocortical representation evolves over time.

Preferential replay

The hippocampus may allow the general statistics of the environment to be circumvented by reweighting experiences such that statistically unusual but significant events may be afforded privileged status. This not only leads to preferential storage and/or stabilization but also results in preferential replay, subsequently shaping neocortical learning.

Consciousness as a Memory System [3]

Consciousness

Phenomenal consciousness is the subjective experience we undergo during an event, while access consciousness refers to when representations become available for cognitive processing. There seems to be a close connection between a mental state being conscious and its contents being available for reporting to others or for use in making rational choices. For instance, we were phenomenally conscious of the sounds of the clock and the earlier part of this sentence, but our access to consciousness occurred only later. The 'hard problem' of consciousness addresses how a collection of biological material can give rise to the subjective experience we call consciousness.

In relation to memory

In reality, we do not directly perceive anything consciously; instead, we experience a memory of a perception. Our conscious decisions and actions are, in fact, recollections of unconscious decisions and actions. We only become aware of the conscious decision or action after the fact. Consciousness may be a component of the episodic memory system, allowing us to mentally time-travel and re-experience past moments, often associated with emotional value (although some argue that conscious memory can be categorized into semantic and episodic memory). In contrast, the ability to derive general facts from specific events is attributed to semantic memory.

Associative Transformer [5]

There is no completely general-purpose learning algorithm, and any learning algorithm will generalize better on some distributions and worse on others [6]. Although transformers proposed a general-purpose architecture in which inductive biases shaping the flow of information are learned from the data itself, there is still the possibility of adding third-order control of the information flow.

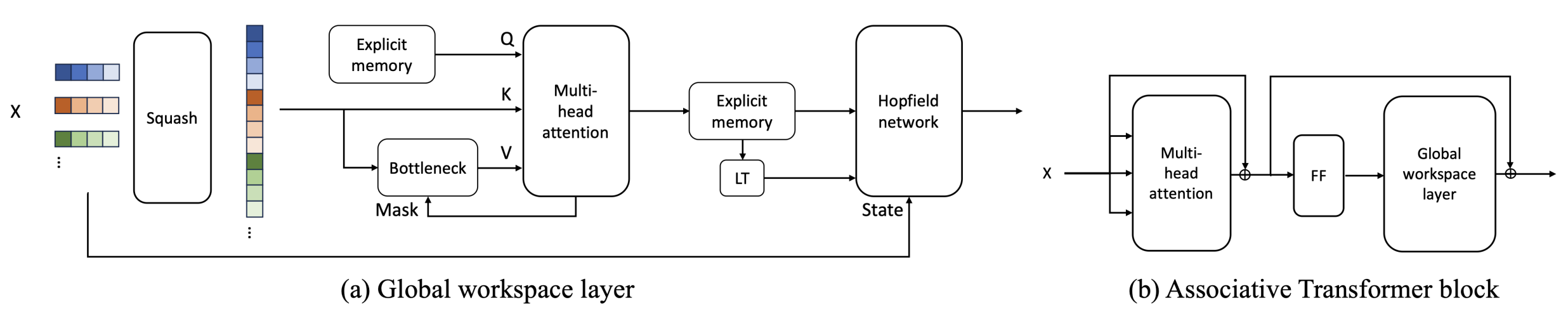

Associative Transformer (AiT) induces low-rank explicit memory that serves as both priors to guide bottleneck attention in the shared workspace and attractors within associative memory of a Hopfield network (Figure 4). Through joint end-to-end training, these priors naturally develop module specialization, each contributing a distinct inductive bias to form attention bottlenecks. A bottleneck can foster competition among inputs for writing information into the memory. We show that AiT is a sparse representation learner, learning distinct priors through the bottlenecks that are complexity-invariant to input quantities and dimensions. AiT has demonstrated its superiority over a wide range of methods such as the Set Transformer and the Coordination method.

Squash layer

In pairwise self-attention, patches from the same sample are attended to. We improve the diversity in patch-wise correlation learning beyond one sample using a squash layer. The squash layer concatenates $N$ patches $V\in\mathbb{R}^{B\times N\times E}$ within one batch $B$ into vectors $V\in\mathbb{R}^{(B\times N)\times E}$, which forms a list of patches regardless of the samples they are from. Since the bottleneck with a fixed capacity $k$ decreases the complexity from $O((B\times N)^2)$ to $O((B\times N)\times k)$, using the squash layer will not add up to the complexity, but increase the diversity of input patches.

Low-rank explicit memory

An explicit memory bank with limited slots aims to learn $M$ priors $\gamma = \mathbb{R}^{M\times D}$ where $D$ is the dimension of the prior. The priors in the memory bank are used as various keys to compute the bottleneck attentions that extract different sets of patches from the squashed input. Further using low-rank priors can reduce memory consumption, whose lower dimension $D << E$ is obtained by applying a down-scale linear transformation on the input patch dimension $E$.

Bottleneck attention with a limited capacity

The objective of the bottleneck attention is to learn a set of priors that guide attention to various sets of input patches. This is enabled by a cross-attention mechanism constrained by hard attention. We first consider a tailored cross-attention mechanism to update the memory bank based on the squashed input $\Xi^t = V^t\in\mathbb{R}^{(B\times N)\times E}$, then we discuss the case of limiting the capacity via a top-$k$ hard attention. Notably, in the cross-attention, the query is a function $W^Q$ of the current memory content $\gamma^t = \{\gamma^t_i\}_{i=1}^M$. The key and value are functions $W^K$ and $W^V$ of the squashed input $\Xi^t$. The attention scores for head $i$ can be computed by $\text{A}^t_i(\gamma^t, \Xi^t)=\text{softmax}(\frac{\gamma^tW^Q_{i,t}(\Xi^tW^K_{i,t})^T}{\sqrt{D}})$.

The hard attention allows patches to compete to enter the workspace through a $k$-size bottleneck, fostering essential patches to be selected. In particular, we select the top-$k$ patches with the highest attention scores from $A^t_i$. The priors in the memory are then updated based on the top-$k$ patches.

Moreover, to ensure a stable update of these priors across different time steps, we employ the layer normalization and the exponentially weighted moving average as follows

$$ \text{head}^t_i = \text{top-}k(\text{A}^t_i)\Xi^tW^V_t,\,\, $$ $$ \hat{\gamma}^{t}=\text{LN}(\text{Concat}(\text{head}^t_1,\dots,\text{head}^t_A)W^O), $$ $$\gamma^{t+1} = (1 - \alpha) \cdot \gamma^{t} + \alpha \cdot \hat{\gamma}^{t},\,\,$$ $$\gamma^{t+1} = \frac{{\gamma^{t+1}}}{{\sqrt{\sum_{{j=1}}^{M} (\gamma^{t+1}_j)^2}}}, $$where top-$k$ is a function to select the $k$ highest attention scores and set the other scores to zero, LN is the layer normalization function, and $\alpha$ is a smoothing factor.

Bottleneck attention balance loss

Employing multiple global workspace layers cascaded in depth leads to the difficulty in the emergence of specialized priors in the explicit memory. To overcome this challenge, we propose the bottleneck attention balance loss to encourage the selection of diverse patches from different input positions in the shared workspace. $\ell_{\text{bottleneck}}$ comprises two components, i.e., the accumulative attention scores and the chosen instances for each input position. Then, we derive the normalized variances of the two metrics across different input positions as follows

$$\ell_{\text{loads}_{i,l}} = \sum_{j=1}^M (\text{A}^t_{i,j,l} > 0),\,\,$$ $$\ell_{\text{importance}_{i,l}} = \sum_{j=1}^M \text{A}^t_{i,j,l},$$ $$\ell_{\text{bottleneck}_{i}} = \frac{{\text{Var}(\{\ell_{\text{importance}_{i,l}}}\}_{l=1}^{B \times N})}{{(\frac{1}{B \times N}\sum_{l=1}^{B \times N}\ell_{\text{importance}_{i,l}}})^2 + \epsilon} + \frac{{\text{Var}(\{\ell_{\text{loads}_{i,l}}}\}_{l=1}^{B \times N})}{{(\frac{1}{B \times N}\sum_{l=1}^{B \times N}\ell_{\text{loads}_{i,l}}})^2 + \epsilon}, $$where $\text{A}^t_{i,j,l}$ denotes the attention score of the input position $l$ for the $j$th memory slot of head $i$, $\ell_{\text{importance}}$ represents the accumulative attention scores in all $M$ memory slots for each input position, $\ell_{\text{loads}}$ represents the accumulative chosen instances for each input position, Var($\cdot$) denotes the variance function, and $\epsilon$ is a small value. The losses for all the heads are summed up as follows $\ell_{\text{bottleneck}} = \sigma\cdot \sum_{i=1}^A\ell_{\text{bottleneck}_i}$ where $\sigma$ is a coefficient.

Information retrieval within associative memory

Attractors

Priors learned in the memory bank act as attractors in associative memory. Attractors have basins of attraction defined by an energy function. Any input state that enters an attractor’s basin of attraction will converge to that attractor. The attractors in associative memory usually have the same dimension as input states, however, the priors $\gamma^{t+1}$ in the memory bank have a lower rank compared to the input. Therefore, we employ a learnable linear transformation $f_{\text{LT}}(\cdot)$ to project the priors into the same dimensional space $E$ of the input before using them as attractors.

Retrieval using an energy function in Hopfield networks

Hopfield networks have demonstrated their potential as a promising approach to constructing associative memory. In particular, we use a continuous Hopfield network operating with continuous input and output values. The upscaled priors $f_{\text{LT}}(\gamma^{t+1})$ are stored within the continuous Hopfield network and subsequently retrieved to reconstruct the input state $\Xi^t\rightarrow \hat{\Xi}^{t}$. Then, we update each patch representation $\xi^t \in \Xi^t$ by decreasing its energy $E(\xi^t)$ within the associative memory as follows

$$ E(\xi^t) = -\text{lse}(\beta,f_{\text{LT}}(\gamma^{t+1}) \xi^t)+\frac{1}{2}\xi^t{\xi^t}^T+\beta^{-1}\text{log}M+\frac{1}{2}\zeta^2, $$ $$ \zeta = \max_{i} |f_{\text{LT}}(\gamma^{t+1}_i)|, $$ $$ \hat{\xi}^t = \arg\min_{\xi^t} E(\xi^t), $$where lse is the log-sum-exp function, $\beta$ is an inverse temperature variable, and $\zeta$ denotes the largest norm of attractors. A skip connection functioning as the information broadcast is employed to obtain the final output $\Xi^{t+1} = \hat{\Xi}^{t} + \Xi^{t}$.