Continual Learning, Compositionality, and Modularity - Part Ⅲ

Created by Yuwei SunAll posts

In information theory, the Kolmogorov complexity is a measure of the computational resources needed to specify an object. Human reasoning identifies abstract patterns from few examples and generalizes them to new inputs through compositional and continual knowledge learning.

Compositional Modularity

- In sequential model fine-tuning, each task of interest requires all the parameters to be fine-tuned based on a specialized model for each task. When multiple tasks share the same model, new information interferes with previously learned knowledge (catastrophic forgetting).

- Even when simultaneously accessing all tasks during training, it is still difficult to balance multiple tasks and train a model that solves each task equally well. In both cases, learning a new task requires a large amount of samples.

- Rather than inducing an abstract representation of the underlying rules in a given task, neural networks tend to overfit to the specific details of the examples observed during training, thus failing to generalize those rules to novel inputs. In contrast, human reasoning is characterized by an ability to identify abstract patterns from only a small number of examples, and to systematically generalize those patterns to novel inputs.

AdapterFusion: Non-Destructive Task Composition for Transfer Learning [1]

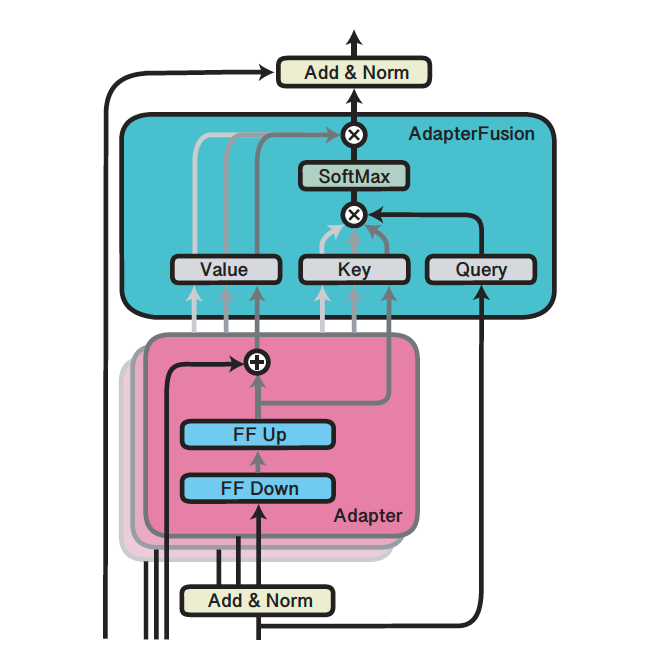

Training independent neural modules for each task prevents knowledge transfer between the task neural modules. AdapterFusion proposes a two-stage learning algorithm that leverages knowledge from multiple tasks. First, in the knowledge extraction stage, it learns task specific parameters of adapters that encapsulate the task-specific information. Then the adapters are combined in a separate knowledge composition step.

- Single-Task Adapters (ST-A): for task $n\in\{1,\dots,N\}$, the model is initialized with parameters $\Theta$. In addition, a set of new and randomly initialized adapter parameters $\Phi_n$ are introduced.

- The parameters $\Theta$ are fixed and only the parameters $\Phi_n$ are trained. The objective for each task $n\in\{1,\dots,N\}$ is of the form, $\Phi_n \leftarrow \arg \min_\Phi \ell(D_n;\Theta,\Phi_n),$ where $D_n$ is a classification dataset.

- Multi-Task Adapters (MT-A): it trains adapters for $N$ tasks in parallel. The globally shared parameters $\Theta$ are finetuned along with the task-specific parameters $\Phi_n$, i.e., $\Theta, \Phi \leftarrow \arg \min_{\Theta, \Phi} \sum_{n=1}^N \ell(D_n; \Theta, \Phi_n).$

- AdapterFusion learns a set of adapters based on the Single-Task Adapters or Multi-Task Adapters to encapsulate the task-specific information. Then, in the knowledge composition stage, the set of $N$ Adapters are combined by using additional parameters $\Psi$. The additional parameters $\Psi_n$ for task $n$ are defined as: $\Psi_n \leftarrow \arg \min_{\Psi_n} \ell(D_n;\Theta,\Phi_1,\dots,\Phi_N,\Psi_n)$.

- They utilized BERT (Devlin et al., 2019) as the pretrained language model in tasks such as commonsense reasoning and sentiment analysis, demonstrating the value in having access to information from other tasks.

I2I: Initializing Adapters with Improvised Knowledge [2]

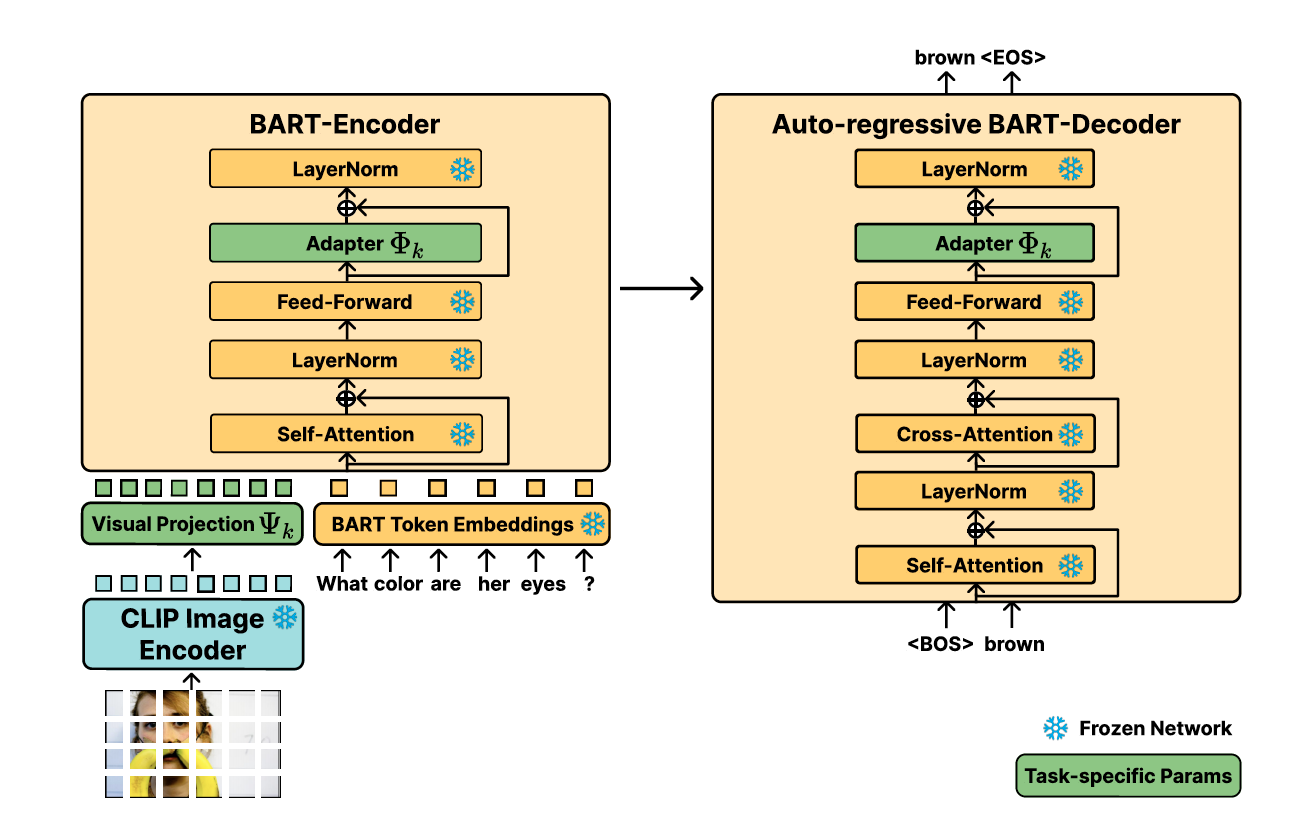

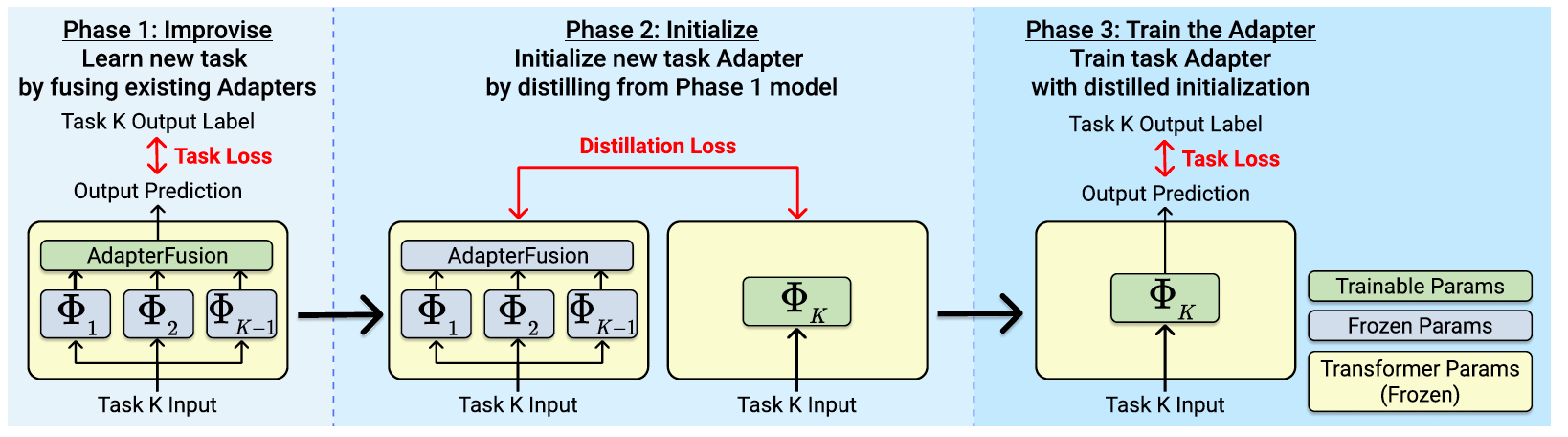

Adding the AdapterFusion layer to the model for each task adds a large parametric cost. Improvise to Initialize (I2I) utilizes knowledge from previously-learned task Adapters to learn an initialization for the incoming visual question answering task’s Adapter module, where the initialized Adapter is trained on the new task. They show that fusing knowledge from existing tasks to learn an initialization yields positive knowledge transfer among tasks compared to AdapterFusion’s post-hoc knowledge composition.

Improvise

I2I improvises on the new task, using knowledge from the already-trained Adapters by minimizing the training loss $\mathcal{L}$ on the dataset $\mathcal{D}_k$ by learning task-specific parameters $\Psi$ an a Fusion layer $\mathcal{F}(\Phi_1,\dots,\Phi_{k-1})$.

$$\mathcal{F}_k,\Psi_k\leftarrow\arg \min_{\mathcal{F},\Psi}\mathcal{L}(\mathcal{D}_k;\mathcal{M}_0,\mathcal{F}(\Phi_1,\dots,\Phi_{k-1}), \Psi).$$Initialize

Then, a new Adapter $\Phi_k$ is initialized by distilling knowledge from the model trained in the Improvise phase. The teacher model $\mathcal{M}_T$ is the previously-learned model with the Fusion layer $\mathcal{F}_k(\Phi_1,\dots,\Phi_{k-1})$. The student model $\mathcal{M}_T$ is a new Adapter $\Phi_k$ inserted inside the pre-trained Transformer $\mathcal{M}_0$. The task-specific parameters $\Psi_k$ for the student model are copied from the teacher model.

During distillation, the student model is trained to produce the same representations as the frozen teacher model by minimizing a distillation loss $\mathcal{L}_D$.

$$\Phi_k, \Psi_k \leftarrow \arg \min_{\Phi,\Psi} \mathcal{L}_D(\mathcal{M}_T(x),\mathcal{M}_S(x)).$$Train the Adapter

The Adapter is trained on task $T_k$, using the Adapter and task-specific parameters from the learned student model as the initial checkpoint.

$$\Phi_k, \Psi_k \leftarrow \arg \min_{\Phi} \mathcal{L}(\mathcal{D}_k;\mathcal{M}_0,\Phi,\Psi).$$Using a separate adapter module for each task can become costly as the number of tasks increases. Future work could explore how the distillation-based methods can mitigate the memory costs of model expansion.

Pushing Mixture of Experts to the Limit: Extremely Parameter Efficient MoE for Instruction Tuning [3]

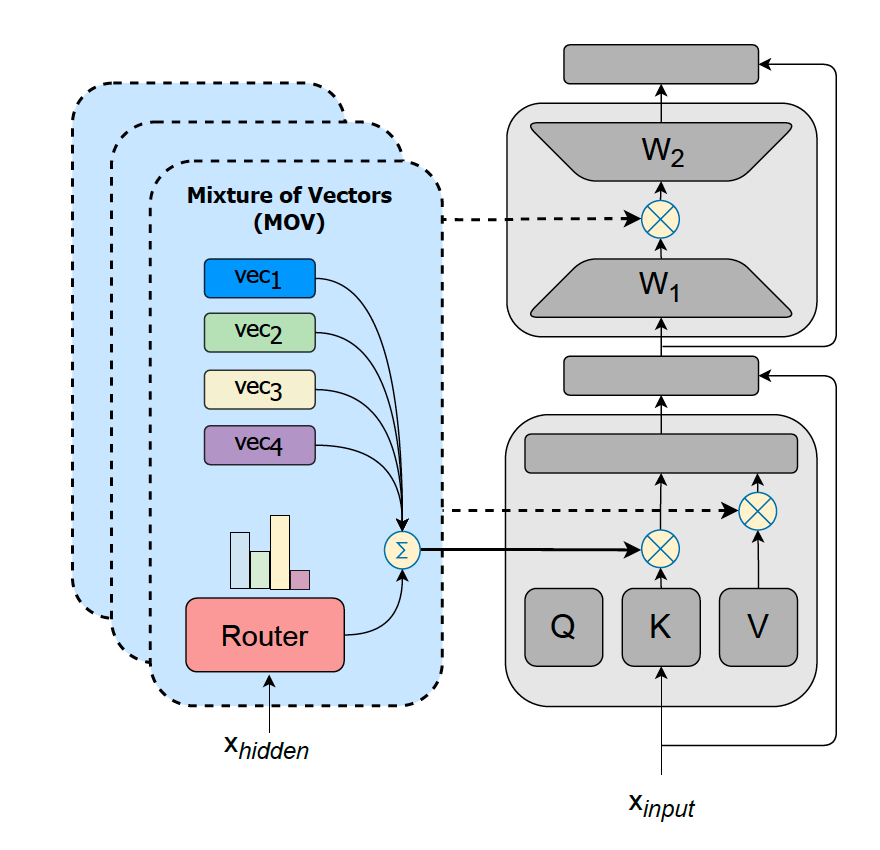

- This work proposed parameter-efficient Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) by combining lightweight experts based on (IA)$^3$ [4] or LORA [5].

- The setting is similar to the Single-Task Adapters setting in AdapterFusion. However, they utilized lightweight experts instead of additional dense layers in Transformers and combined the two-step learning.

- The pretrained weights of Transformers remain fixed, while experts and router parameters are trained from scratch.

- The experiments showed that increasing the number of experts generally improved unseen task performance.

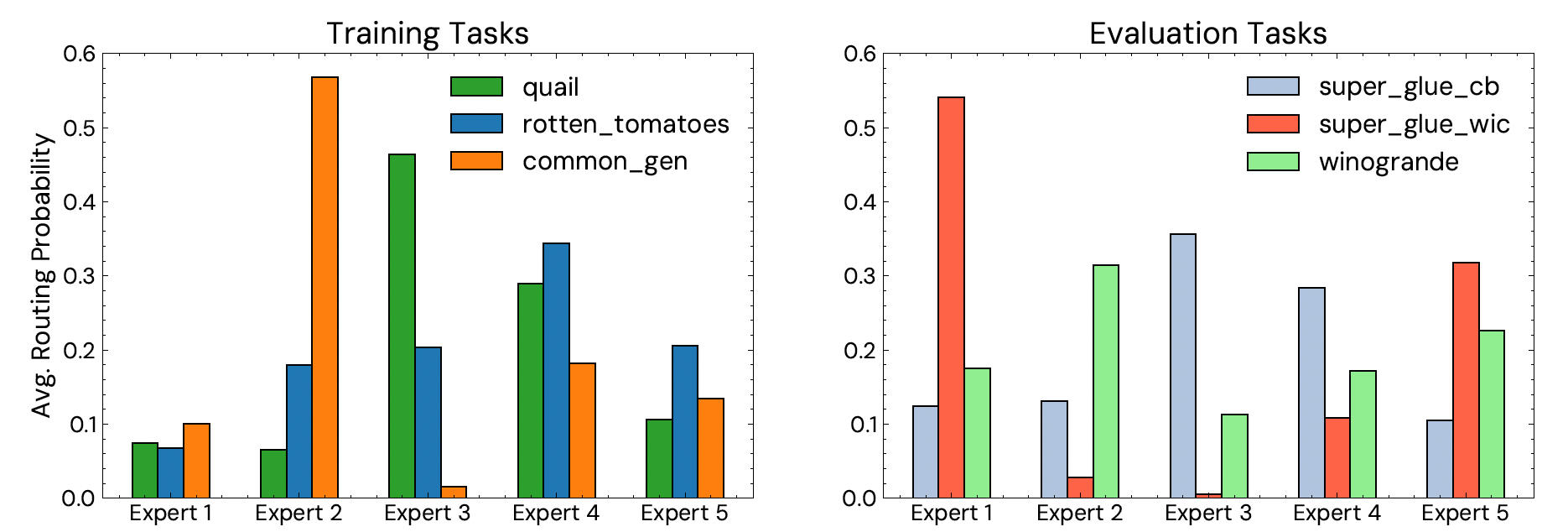

- Expert specialization: the mean routing probabilities in the last decoder block were plot to understand cross-task generalization.

Curriculum Learning

- Research in developmental psychology [6] demonstrates that human infants slowly learn their first words, and this learning then enables them to learn words in one trial. The development of increasingly sophisticated representations extends beyond the grammar of natural languages to other symbolic processing in human activities such as explicit planning and mathematics.

- Curriculum learning [7] introduces the concept of guiding the optimization process, either to achieve faster convergence or to steer the learner toward better local minima.

Voyager: An Embodied Curriculum Learner [8]

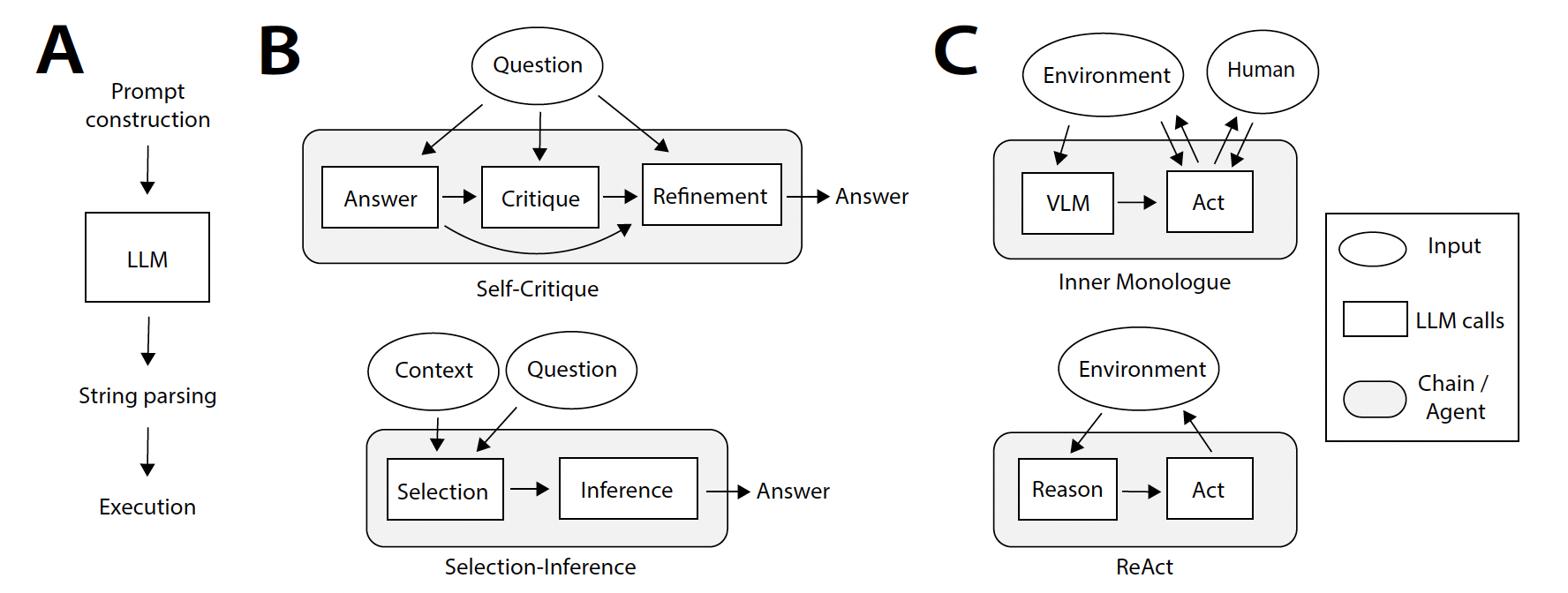

Large Language Models (LLMs)-based agents like Auto-GPT and BabyAGI can exhibit reasoning and planning abilities similar to the symbolic processing using techniques such as Chain-of-Thought (CoT) and problem decomposition. These agents operate by receiving a task, running in a loop to break the task into subtasks, prompting themselves, responding to the prompts, and repeating the process until the goal is achieved. However, LLMs generate symbols directly as output, whereas human conscious thoughts are intermediate quantities, better understood as unobserved (latent) random variables. Moreover, LLMs typically lack high-dimensional sensory inputs and possess a memory limited to a finite number of past interactions. In contrast, humans have a recursively defined internal state capable of retaining information from moments arbitrarily far in the past.

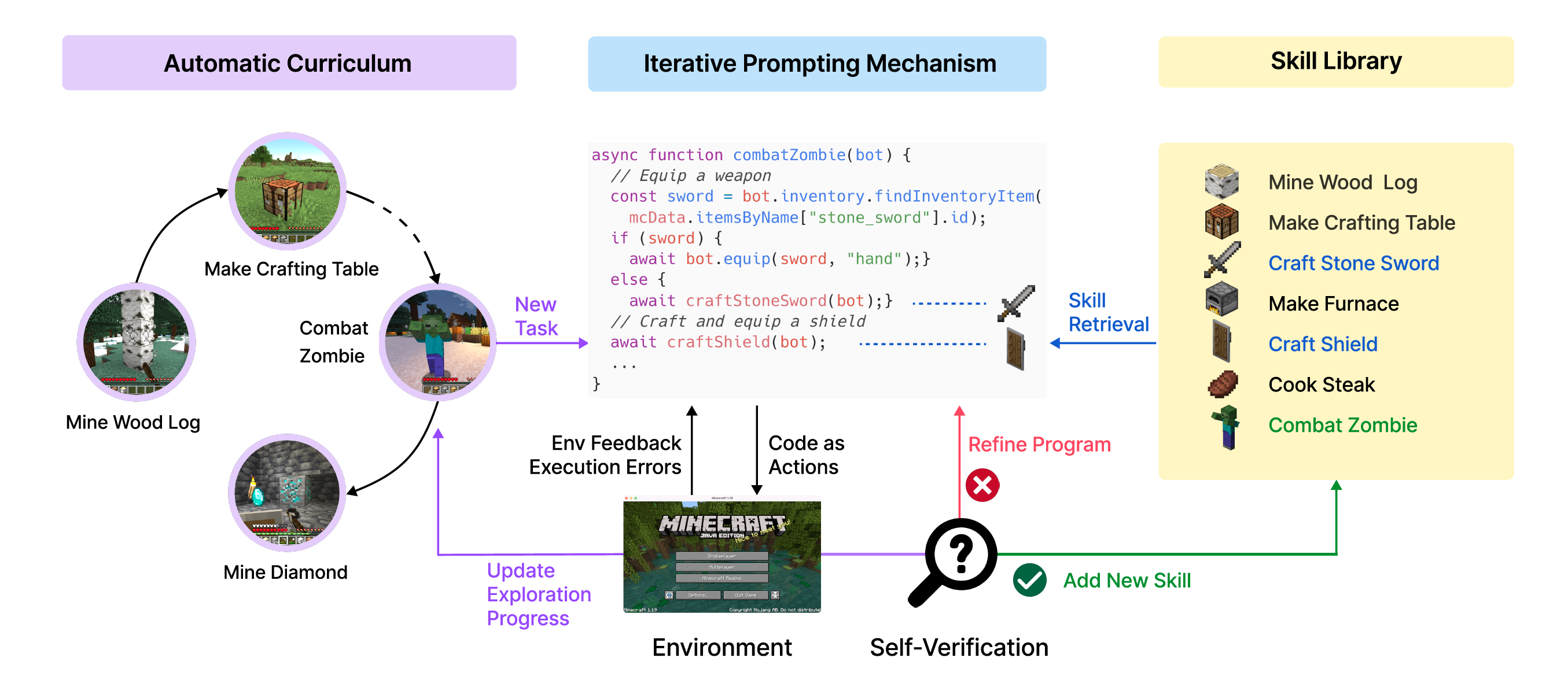

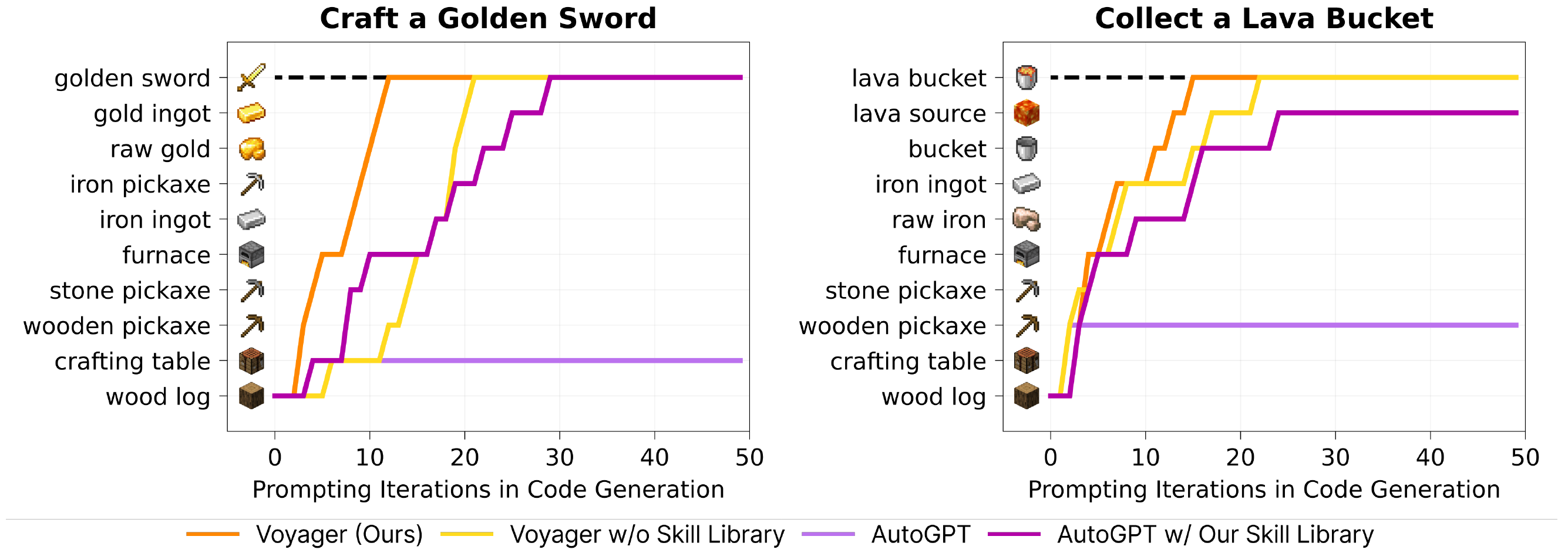

Voyager addresses progressively harder tasks proposed by the automatic curriculum, progressively acquiring, updating, accumulating, and transferring knowledge over extended time spans. This approach not only rapidly enhances capabilities but also effectively counters catastrophic forgetting.

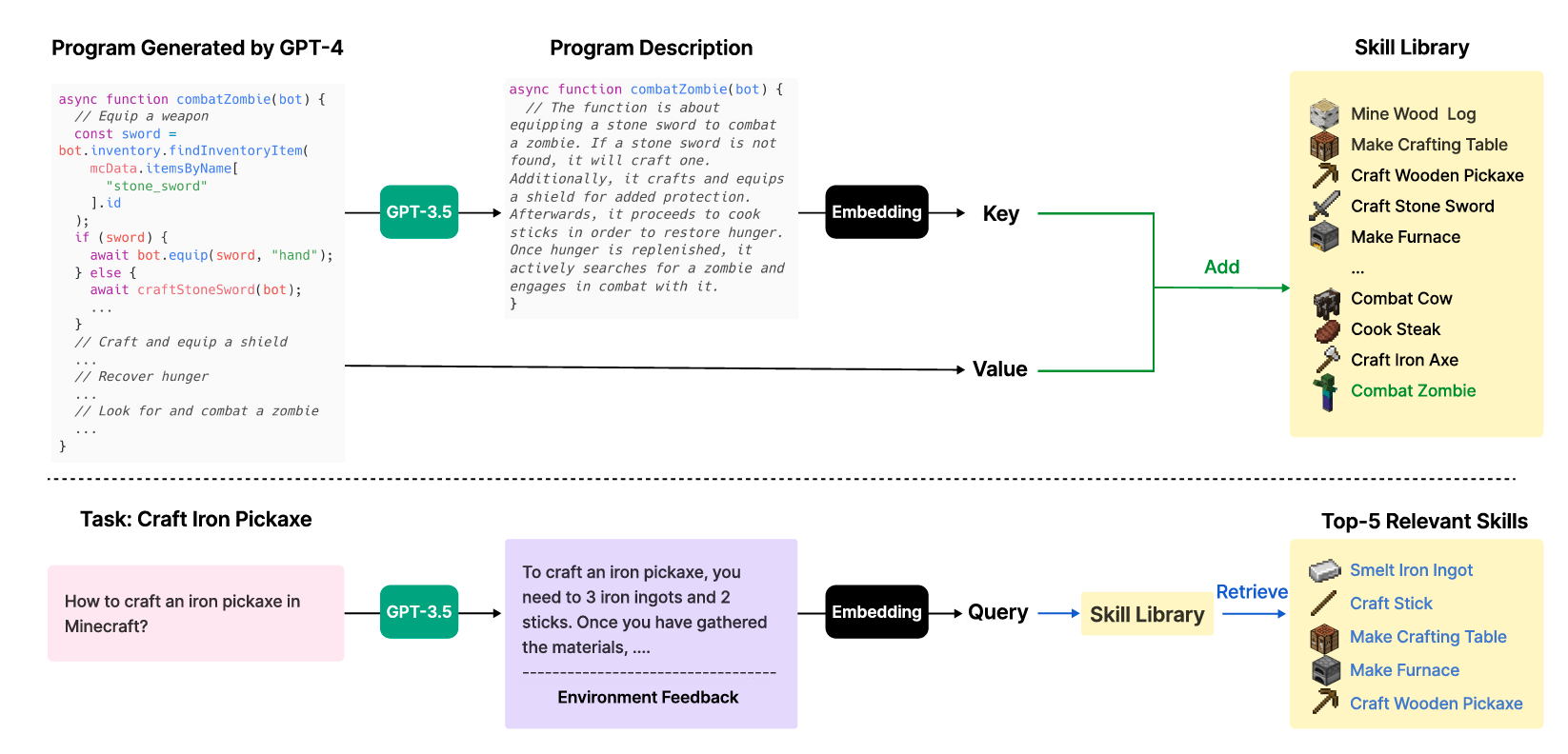

The automatic curriculum, which considers the exploration progress and the agent’s state, is generated by GPT-4 based on the overarching goal of "discovering as many diverse things as possible." This approach can be perceived as an in-context form of novelty search. VOYAGER incrementally builds a skill library by storing the action programs that help solve tasks successfully.

Each program is indexed by the embedding of its description, allowing it to be retrieved in similar situations in the future. Complex skills can be synthesized by composing simpler programs, which rapidly enhances VOYAGER’s capabilities over time and alleviates catastrophic forgetting common in other continual learning methods.

Their simulation environment is built on top of MineDojo [10] and leverages Mineflayer JavaScript APIs for motor controls. VOYAGER does not support visual perception, as the available version of the GPT-4 API was text-only.

VOYAGER demonstrates significantly better exploration capabilities. VOYAGER consistently makes new strides, discovering 63 unique items within 160 prompting iterations—3.3 times more novel items compared to its counterparts; VOYAGER unlocks the wooden level 15.3 times faster (in terms of prompting iterations), the stone level 8.5 times faster, the iron level 6.4 times faster, and is the only one to unlock the diamond level of the tech tree; In terms of map traversal, VOYAGER navigates distances 2.3 times longer compared to baselines by traversing a variety of terrains. In addition, despite the iterative prompting mechanism, there are instances where the agent gets stuck and fails to generate the correct skill, where the automatic curriculum is utilized to reattempt these tasks at a later time.

Long-Term Memory

HippoRAG: Neurobiologically Inspired Long-Term Memory for Large Language Models [11]

A continuously updating long-term memory is still absent from current AI systems. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) integrates large language models (LLMs) with external knowledge sources. However, even with RAG, LLMs still struggle to efficiently and effectively integrate a large amount of new experiences after pre-training.

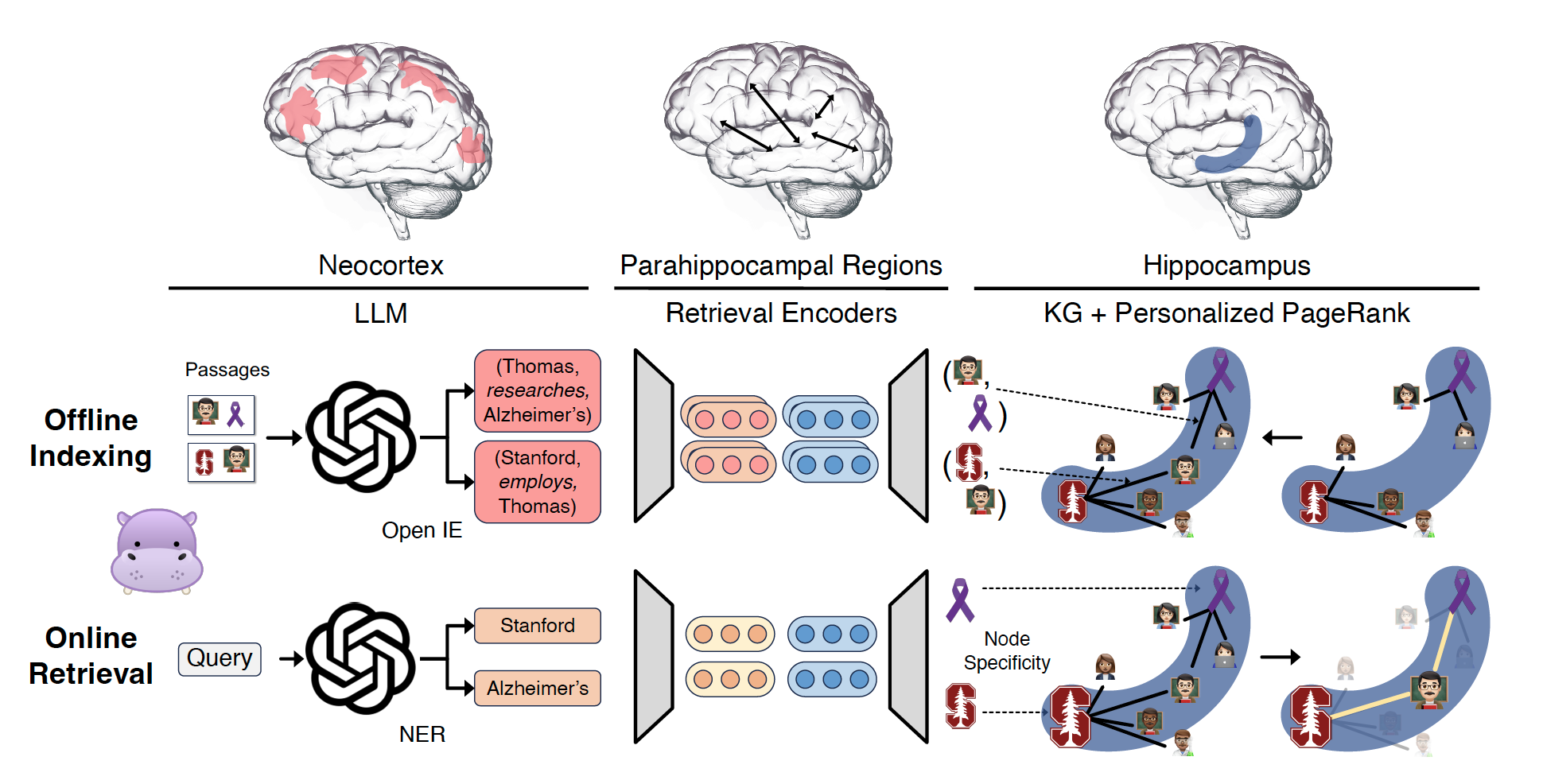

Hippocampal Memory Indexing Theory: Context-based, continually updating memory relies on interactions between the neocortex, which processes and stores actual memory representations, and the C-shaped hippocampus, which holds the hippocampal index. The hippocampal index is a set of interconnected indices that point to memory units in the neocortex and stores associations between them.

HippoRAG, inspired by the hippocampal indexing theory of human long-term memory, enables deeper and more efficient knowledge integration over new experiences. It uses knowledge graphs and the Personalized PageRank algorithm to mimic the different roles of the neocortex and hippocampus in human memory. A major advantage of HippoRAG over conventional RAG methods in multi-hop question answering is its ability to perform multi-hop retrieval in a single step.

HippoRAG leverages pattern separation and pattern completion. The pattern separation ensures that the representations of distinct perceptual experiences are unique. This process is primarily accomplished in memory encoding, which starts with the neocortex receiving and processing perceptual stimuli into more easily manipulable, likely higher-level features, and then routed through the parahippocampal regions (PHR) to be indexed by the hippocampus. When these stimuli reach the hippocampus, salient signals are included in the hippocampal index and associated with each other. The pattern completion enables the retrieval of complete memories from partial stimuli. Given a new query, HippoRAG identifies the key concepts in the query and runs the Personalized PageRank (PPR) algorithm on the Knowledge Graph (KG), using the query concepts to integrate information across passages for retrieval.

Offline Indexing

During this phase, an instruction-tuned LLM extracts a set of \( N \) named entities \(\{e_1, \cdots, e_n\}\) and their relational edges \( E \) from each passage via OpenIE. Then, a set of retrieval encoders \( M \) adds an extra set of synonymy relations \( E' \) when the cosine similarity between two entity representations in \(\{e_1, \cdots, e_n\}\) is above a threshold \(\tau\). This process introduces more edges to the hippocampal index and allows for more effective pattern completion.

Online Retrieval

From a query \( q \), a set of named entities \(\{c_1, \cdots, c_n\}\) are extracted by the LLM. Then, a set of query nodes \( R_q = \{r_1, \dots, r_n\} \) is chosen as the set of nodes \(\{e_1, \cdots, e_n\}\) from the offline indexing with the highest cosine similarity. That is, \( r_i = e_j \) where \( j = \arg\max_j \text{cosine}(M(c_i), M(e_j)) \). After the query nodes \( R_q \) are found, the Personalized PageRank (PPR) algorithm is performed over the hippocampal index to obtain a probability distribution for the eventual retrieval.

Remembering Transformer for Continual Learning [12]

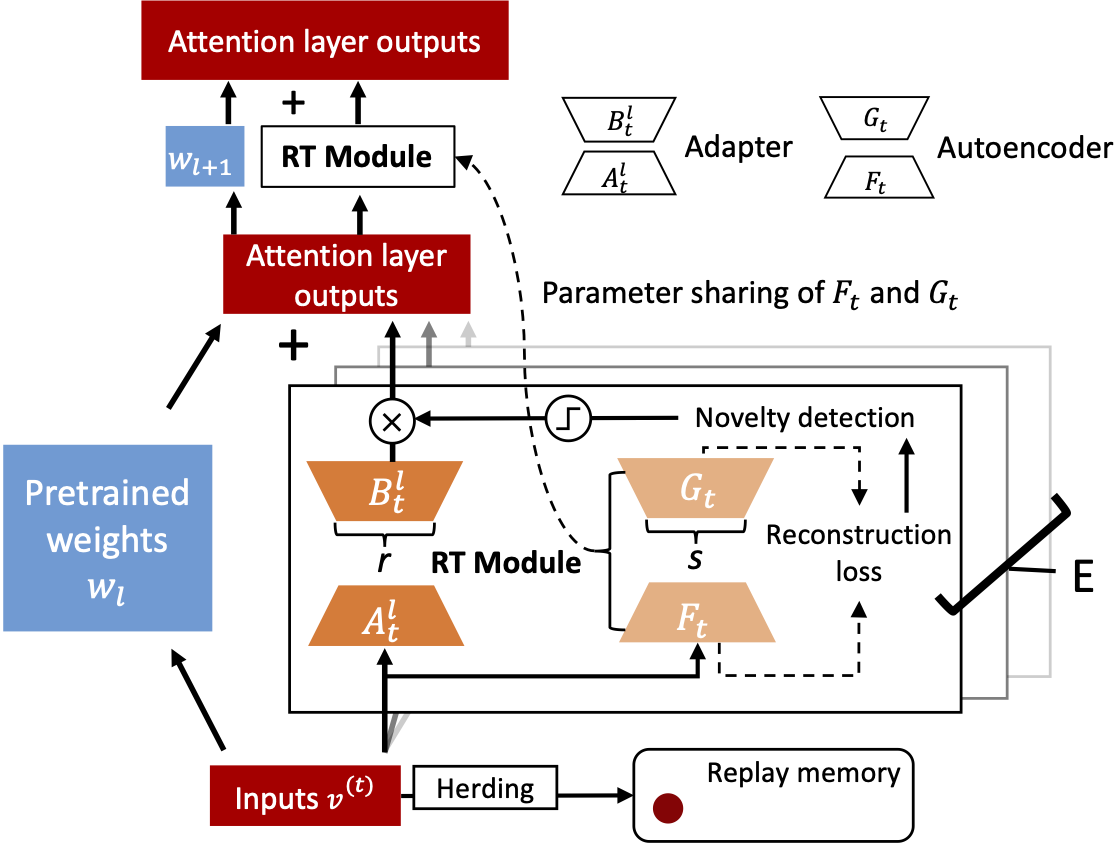

In Complementary Learning Systems (CLS) Theory [13], Hippocampus rapidly encodes task data and consolidates the task knowledge into the Neocortex by forming new neural connections. Hippocampus developed a novelty detection mechanism to facilitate consolidation by switching among neural modules for various tasks. Inspired by the CLS theory, Remembering Transformer leverages the mixture-of-adapters that are sparsely activated with a novelty detection mechanism in a pretrained Transformer.

Mixture-of-Adapters in Vision Transformer

For each task $T^{(t)}\subseteq T$, LoRA is employed for efficient fine-tuning with low-rank decomposition matrices. The trainable decomposition matrices are applied to the attention weights of ViT's different layers. For each attention layer $l$, linear transformations are applied to the query, key, value, and output weights ($W_l^Q, W_l^K, W_l^V, W_l^O$). For $W_l \in \mathbb{R}^{D\times D}$ $\in$ ($W_l^Q, W_l^K, W_l^V, W_l^O$), the parameter update $\Delta W_l$ is then computed by $W_l + \Delta W_l = W_l + B^lA^l$, where $A^l\in \mathbb{R}^{D\times r}, B^l \in \mathbb{R}^{r\times D}$, and $r$ is a low rank $r \ll D$. For an input token $v^{(t)}$, the output of the $l$th attention layer is $\hat{W_l}v^{(t)} + \Delta W_lv^{(t)} = \hat{W_l}v^{(t)} + B^lA^lv^{(t)}$ where $\hat{\cdot}$ indicates untrainable parameters. For each task $T^{(t)}$, $\theta^t_{\text{adapter}} = \{A_t^l, B_t^l\}_{l=1}^L$ is added to ViT $\{\theta_{\text{ViT}},\theta^t_{\text{adapter}}\}$.

Generative Routing

A generative model encodes tokens from a specific task and assesses the familiarity of a new task in relation to the encoded knowledge of the old task. A low-rank autoencoder (AE) $\theta_{\text{AE}}$ that consists of an encoder and decoder is utilized, each of which leverages one linear transformation layer $F \in \mathbb{R}^{D\times s}$ and $G \in \mathbb{R}^{s\times D}$ where $s$ is a low rank $s \ll D$. The AE encodes tokens of the embedding layer output $V^{(t)}$, which are flattened and passed through a Sigmoid activation $\sigma(\cdot)$, $\hat{V^{(t)}} = GF\sigma(V^{(t)})$. Then, the AE is updated based on the mean squared error loss.

$$\ell_t(\theta_{\text{AE}}) = ( \sigma((V^{(t)}) - \hat{V^{(t)}})^2,\\ \hat{\theta}_{\text{AE}} =\underset{\theta_{\text{AE}}}{\text{arg min }}\ell_t.$$During inference, the autoencoders, each encoding different task knowledge, predict routing weights to allocate a sample to the most relevant adapter.

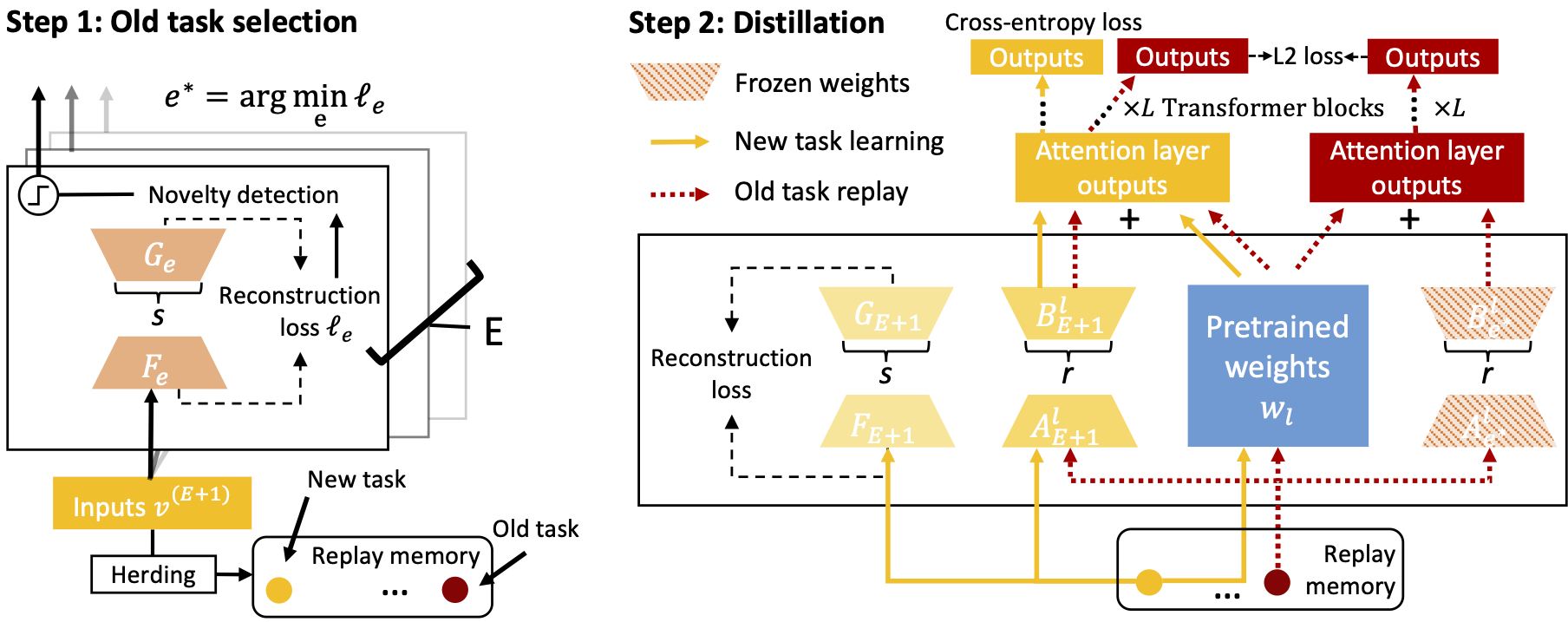

$$\ell_e = ( \sigma(v) - \hat{G}_e\hat{F}_e\sigma(v))^2,\\ e^*=\underset{e}{\text{arg min }}\ell_e,\\ W_g(e) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } e = e^* \\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}$$Knowledge Distillation

The aim is to aggregate similar adapters through knowledge distillation that transfers the knowledge of a selected old adapter $\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{e^*}$ to the new adapter $\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{t}$ when the model capacity $E$ for new adapters is reached, i.e., $t=E+1$. The old adapter $e^*$ for knowledge distillation is selected based on the reconstruction loss. The soft probability output of the old adapter when taking its replay memory samples $\Xi_{e^*}$ as input is computed by $f(\Xi_{e^*};\{\hat{\theta}_{\text{ViT}},\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{e^*}\})$. Then, the new adapter $\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{E+1}$ is updated based on both the new task $\{V^{E+1},Y^{E+1}\}$ and the replay memory of the old task $\{\Xi_{e^*}, f(\Xi_{e^*};\{\hat{\theta}_{\text{ViT}},\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{e^*}\})\}$.The cross-entropy loss $\ell_\text{CE}(\cdot)$ and the L2 loss $\ell_\text{L2}(\cdot)$ is utilized for training on the new and old tasks, respectively.

$$\ell_\text{CE} = -\sum_{i=1}^{K_{E+1}} f(x_i^{E+1};\{\hat{\theta}_{\text{ViT}},\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{E+1}\}) \log(y^{E+1}_i),$$ $$\ell_\text{L2} = \sum_{i=1}^{M}(f(v^{e^*}_i; \{\hat{\theta}_{\text{ViT}},\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{e^*}\}) - f(v^{e^*}_i;\{\hat{\theta}_{\text{ViT}},\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{E+1}\}))^2,$$ $$\hat{\theta}_{\text{adapter}}^{E+1} = \underset{\theta_{\text{adapter}}^{E+1}}{\text{arg min }}\alpha\cdot\ell_\text{CE}+ (1-\alpha)\cdot\ell_\text{L2},$$where $\alpha$ is a coefficient to balance the two loss items. After the knowledge distillation, the old adapter $e^*$ is removed and the old task is rerouted to the newly learned adapter.

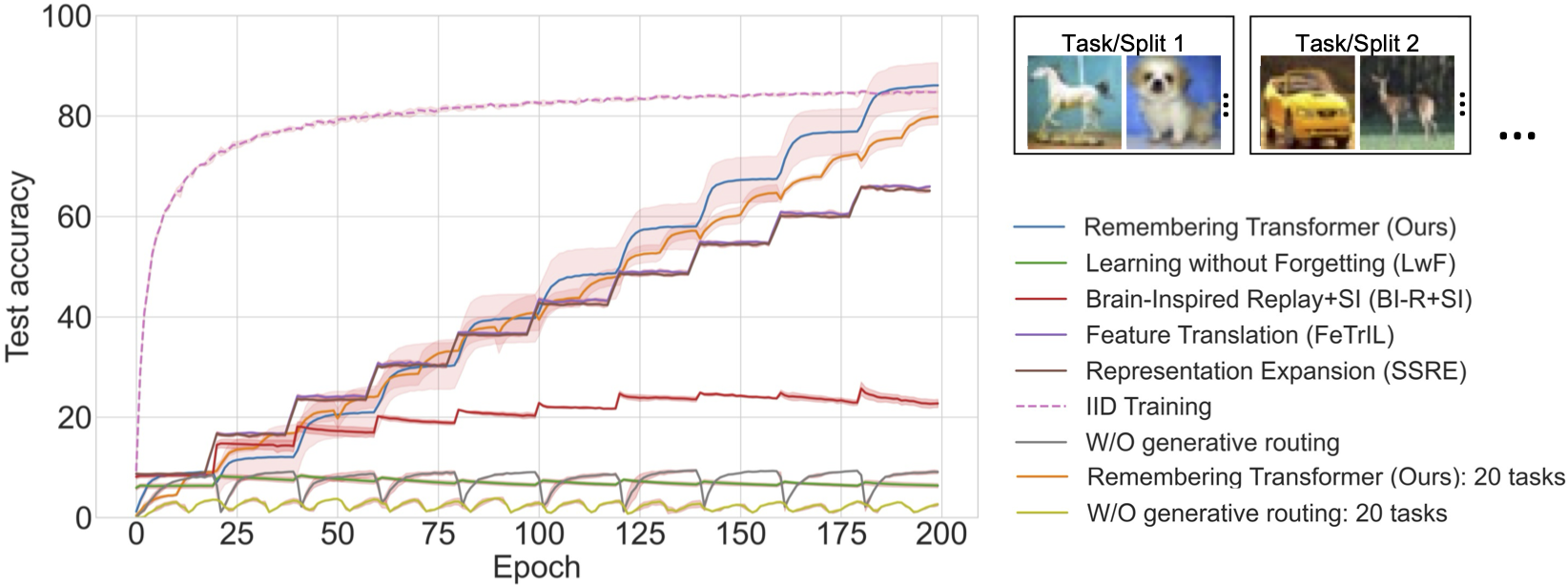

Continual Learning Tasks

Split task: a dataset is split into several subsets of equal numbers of classes, with each subset as a task. For example, the CIFAR-100 dataset was divided into ten tasks. The first task consists of classes 0 - 9 and the second task consists of classes 10 - 19 and so on. All tasks were trained for $\frac{\text{total epochs}}{\text{# of tasks}}$ epochs before the model training on a different task.

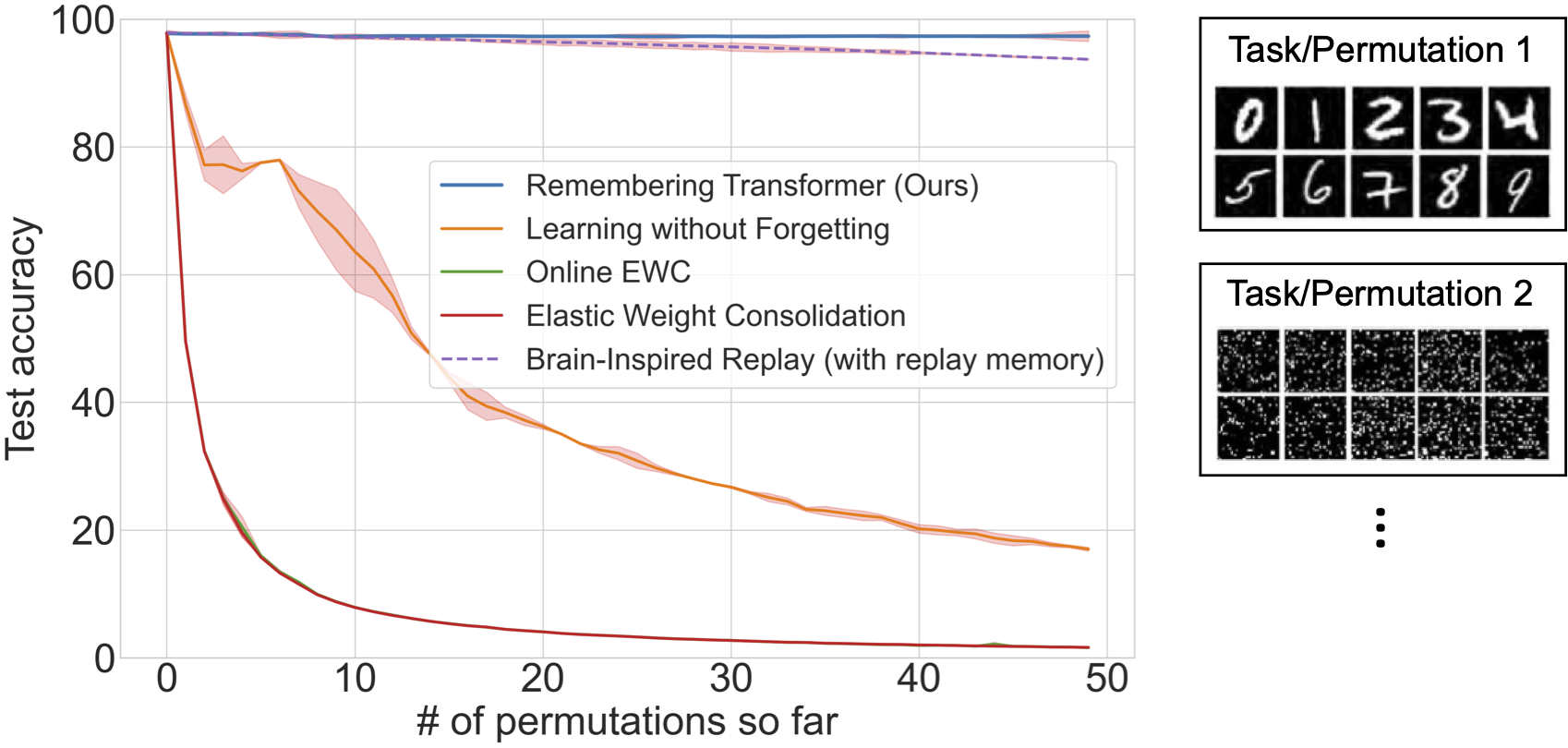

Permutation task: the input pixels of an image are shuffled with a random permutation for each task. Remembering Transformer was evaluated in the permuted-MNIST dataset. Each task consists of all 10 digits, with a specific permutation shift employed to the image pixels. During inference, the model is given samples featuring the same set of permutation patterns but lacks identity information on the various permutations.

Remembering Transformer demonstrated SOTA continual learning task accuracy and parameter efficiency through the mixture-of-adapters and generative routing in ViT.