Global Workspace Theory and System 2 AI - Part Ⅱ

Created by Yuwei SunAll posts

This post is about the alignment between the global workspace theory and Transformer models, with a specific focus on the attention mechanism, since my last post on “Global Workspace Theory and System 2 AI - Part Ⅰ”.

Two-Tier Cognitive Systems

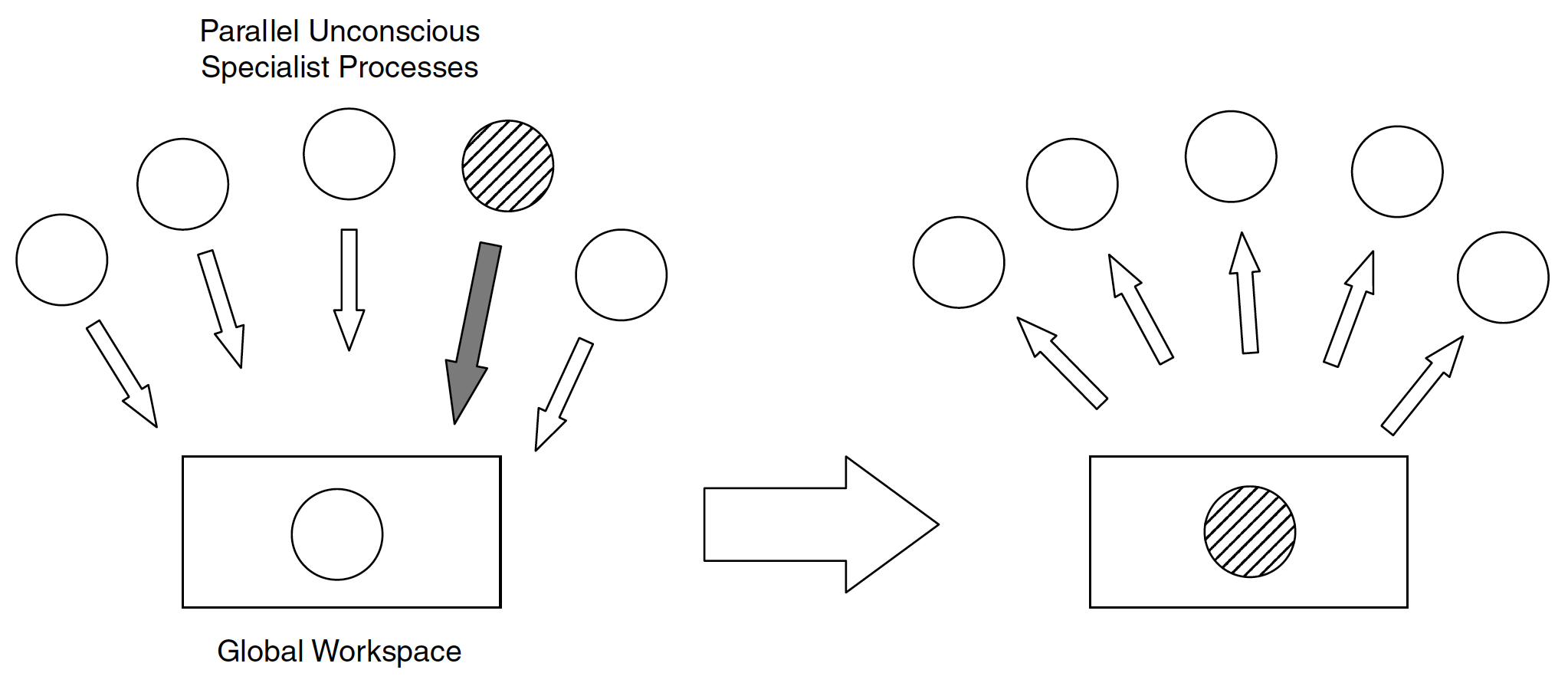

Global Workspace Theory (GWT) [1] proposes that the brain operates as a network of specialized modules, with a central "global workspace" where selected information is integrated and broadcast (Figure 1). In our brain, unconscious processing is where much of our intelligence lies, such as Bayesian inference and evidence accumulation.

Consciousness involves two distinct types of information-processing computations in the brain: (C1) the selection of information for global broadcasting, making it flexibly available for computation and report, and (C2) the self-monitoring of these computations, leading to a subjective sense of certainty or error [2]. Both of these processes rely on the prefrontal cortex. In C1, information that is conscious in this sense becomes globally available to the organism. It involves integrating all available evidence to converge toward a single decision. At the top of a deep hierarchy of specialized modules, a "global workspace" with limited capacity evolved to select a piece of information, hold it over time, and share it across modules. While language is not a prerequisite for conscious processing, the emergence of language circuits in humans may have significantly increased the speed, ease, and flexibility of C1 information sharing.

Furthermore, C2 refers to the self-monitoring ability to conceive and make use of internal representations of one's own knowledge and abilities, the capacity to reflect on one's own mental state. For example, Hallucinations in schizophrenia have been linked to a failure to distinguish whether sensory activity is generated by oneself or by the external world. A machine endowed with C1 and C2 would behave as though it were conscious; for instance, it would know that it is seeing something, express confidence in it, report it to others, and could experience hallucinations when its monitoring mechanisms break down.

Related Work

We evaluate various approaches to implement a global workspace by considering several key factors. Firstly, we examine whether the implementation involves a global workspace operation that facilitates both writing and reading of information. Secondly, we assess whether the memory or information stored within the workspace is low-dimensional compared to the input data. Thirdly, we analyze whether the retrieval of information from the memory is driven by a bottom-up or top-down signal. Lastly, we investigate whether the model incorporates a communication bottleneck to regulate the flow of information passing through the system. By carefully considering these aspects, we gain insights into the effectiveness and efficiency of different global workspace implementations. For information about Vision Transformer, Bidirectional, and Coordination methods, please refer to the previous post on "Global Workspace Theory and System 2 AI - Part Ⅰ".

Attention Mechanism

The self-attention in Transformer employs the multi-head attention mechanism in which each head maps a query and a set of key-values pairs to an output. The output in a single head is computed as a weighted sum of values according to the attention score computed by a function of the query with the corresponding key. These single-head outputs are then concatenated and again projected, resulting in the final values:

$$\mbox{Multi-head}(Q,K,V)=\mbox{Concat}(\mbox{head}^1,\dots,\mbox{head}^H)W^O,$$ $$\mbox{head}^i=\mbox{Attention}(QW^{Q_i},KW^{K_i},VW^{V_i}),$$ $$\mathbf{A_S} = \mbox{Attention}(Q,K,V)=\mbox{softmax}(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d}}),$$ $$\mathbf{A_R}=\mathbf{A_S}\,\mathbf{V},$$where $W^Q,W^K,W^V$ and $W^O$ are linear transformations for queries, keys, values and outputs. $\tilde{Q}= QW^{Q_i}$, $\tilde{K} = KW^{K_i}$, and $\tilde{V} = VW^{V_i}$. $d$ denotes the dimension of queries and keys in a single head. In self-attention, $Q = K = V$. However, this approach has a quadratic complexity $O(N^2)$ where $N$ denotes the number of tokens in an input sequence and can be computationally intensive.

Perceiver [3]

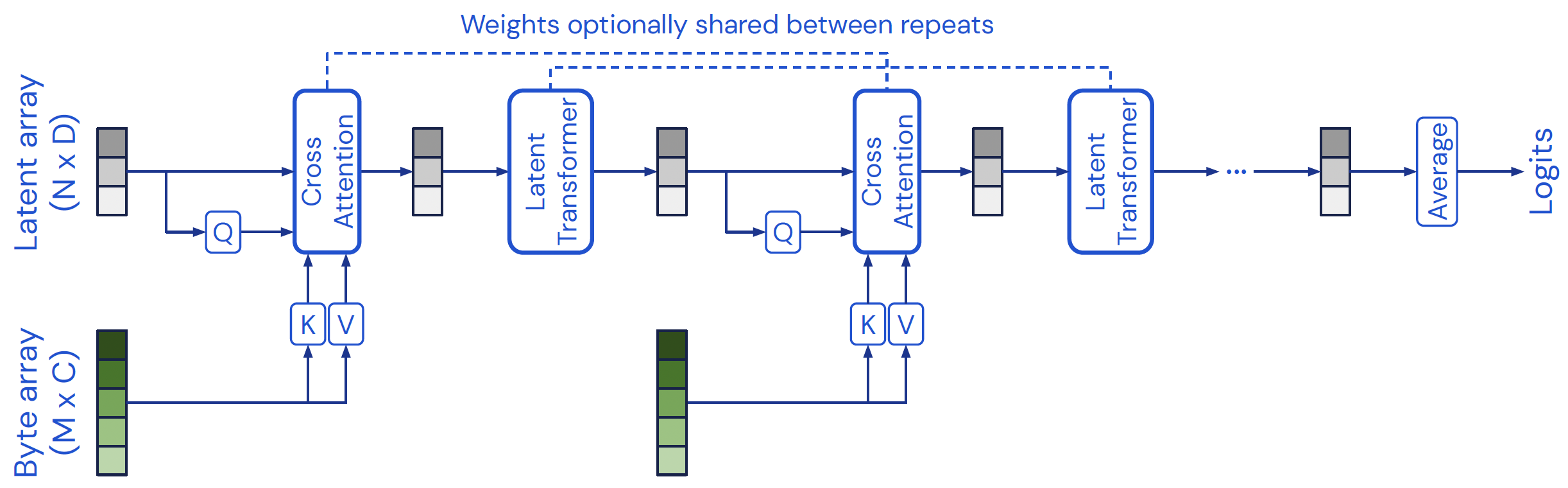

The Perceiver model (Figure 2) builds upon Transformers, using shared attention to process and integrate information from various sources. The Perceiver includes two components: a cross-attention module that maps a byte (input) array and a latent array to a latent array, and a Transformer tower that maps a latent array to a latent array. The bulk of the computation happens in a latent space whose size $N$ is typically much smaller than the inputs and outputs $M$, which makes the process computationally tractable even for very large inputs and outputs.

Let \(K \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times C}\) and \(V \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times C}\) (where \(C\) is channel dimension) be the key and value. \(Q\) is a projection of a learned latent array with index dimension \(N \times D\), where \(N\) is the size of the latent space and $D$ is the dimension of it. The resulting cross-attention operation has complexity \(O(MN)\). Moreover, a latent Transformer that resembles self-attention is employed after the cross attention.

By using iterative attention with the cross attention and latent Transformer, the Perceiver effectively captures complex patterns and dependencies across the input and output domains. The Perceiver obtains performance comparable to ResNet-50 and Vision Transformer on ImageNet without 2D convolutions. It is also competitive in all modalities in AudioSet.

Perceiver IO [4]

Building upon the Perceiver model, the Perceiver IO (Figure 3) differs from its predecessor in the following aspects: Perceiver IO introduces an encoder and decoder architecture. In the decoder part, the query originates from the output array of the cross-attention mechanism, while the key and value components are derived from the latent array. Conversely, in the original Perceiver model, the query is sourced from the latent array, and the key and value components are extracted from the input array. This fundamental change in the attention mechanism allows for a top-down attention with more expressive and flexible information flow within the model.

Set Transformer [5]

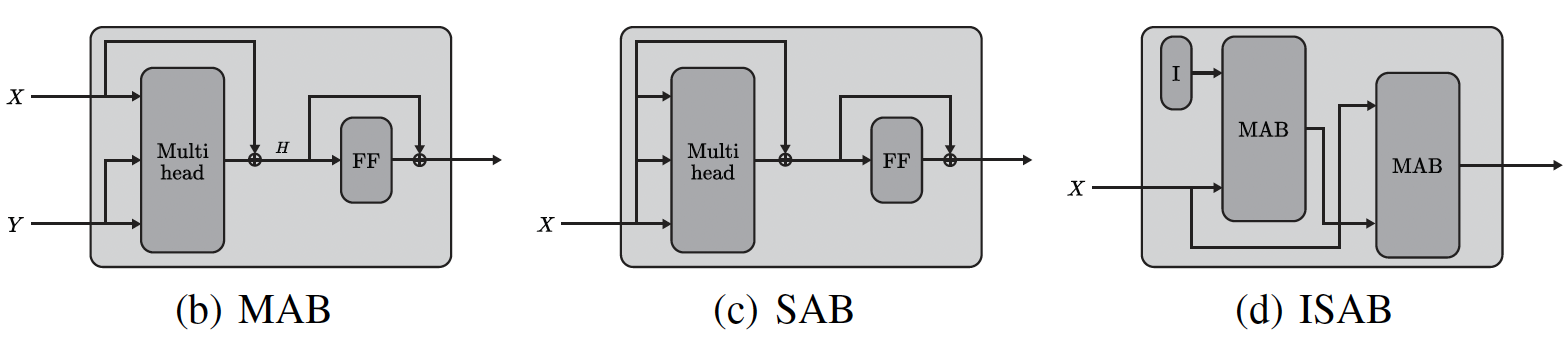

The Set Transformer introduces the Induced Set Attention Block (ISAB) (Figure 4) to reduce the computational time of self-attention from quadratic to linear in the number of elements in a set. This is accomplished by transforming the inducing points \(I\) through an attention mechanism that attends to the input set \(X\). The resulting transformed set is then subjected to another attention mechanism that attends to the input set \(X\) once again, ultimately producing a set.

The ISAB is constructed using the Multihead Attention Block (MAB). Given two matrices \(X\) and \(Y\) representing two sets of \(d\)-dimensional vectors with dimensions \(\mathbb{R}^{n \times d}\), the MAB with parameters \(\Theta\) is defined as follows: \[\text{MAB}(X, Y) = \text{LayerNorm}(H + \text{rFF}(H)),\] where \(H = \text{LayerNorm}(X + \text{Multihead}(X, Y, Y, \Theta))\), \(\text{rFF}\) is a feed forward layer, and \(\text{LayerNorm}\) is layer normalization. Then, the ISAB is defined as $\text{ISAB}(X) = \text{MAB}(X, H) \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}$, where \(H = \text{MAB}(I, X) \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times d}\). Moreover, the self-attention is realized by a Set Attention Block (SAB): $\text{SAB}(X) = \text{MAB}(X, X)$.

Linear Unified Nested Attention [6]

Linear Unified Nested Attention (Luna) aims to solve the quadratic complexity problem of full attention. Luna decouples the regular attention function into two nested attention operations, both of which have linear efficiency, with an extra input that is similar to the inducing points in the Set Transformer (Figure 5). Different from the Set Transformer, Luna is used as a drop-in-replacement for the regular attention in Transformer blocks.

Let $P\in \mathbb{R}^{l\times d}$ be the extra input sequence and $X\in \mathbb{R}^{m\times d}$ be the context sequence. Then, we can obtain the output of the pack attention $Y_P\in \mathbb{R}^{l\times d} = \text{Attn}(P,X)$. The complexity of pack attention is $O(lm)$, which is linear with respect to $m$. Moreover, to unpack the sequence back to the length of the original query sequence $X$, Luna leverages its second attention $Y_X = \text{Attn}(X, Y_P)$, where the complexity is $O(ln)$. Additionally, the $P$ is initialized as learnable positional embeddings.

Global Memory Augmentation for Transformers [7]

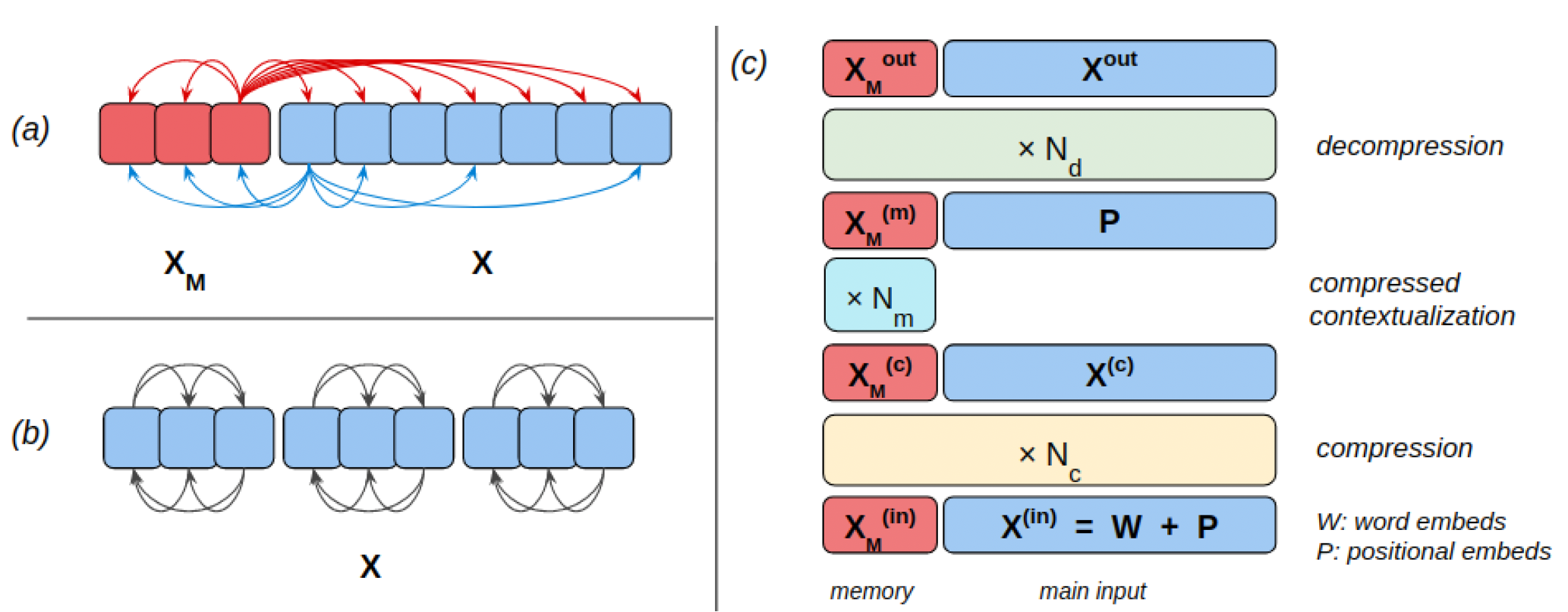

Global Memory Augmentation for Transformers (GMAT) (Figure 6) employ a small global memory which is read and updated by all the positions using vanilla attention. A list of $M$ memory tokens is prefixed to every input sequence (of length $L$) ($M \ll L$). At each multi-head attention layer, for each head, the $L$ tokens attend to other tokens of the main sequence using any sparse variant of attention, whereas they attend to the $M$ memory tokens using dense attention. A sparse attention variant computes a few entries of $QK^T$, masking out the rest. For a binary mask $B \in \{0, -\infty\}^{L_Q\times L_K}$, $\text{SparseAttention}(Q,K,V,B)=\text{softmax}(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d}}+B)V$, where $L_Q$ and $L_K$ are the number of entries for Q and K. Moreover, the $M$ memory tokens attend to all $M+L$ tokens using dense attention.

Consider a $N$-layer GMAT with a memory of size $M$. Given a length $L$ input sequence, let $W$ and $P$ denote its word and positional embeddings. First, the bottom $N_c$ layers are applied for compressing the entire information of the input sequence into just $M$ memory vectors. The next $N_m$ layers are then applied only on the $M$ memory vectors resulting in richer representations. This length $M$ sequence is restored to the original length $M+L$ by concatenating the positional embeddings $P$ and, finally, the remaining $N_d$ layers are applied for decompressing the information packed into the final representations, where the positional embeddings $P$ act as queries for restoring the original input information.

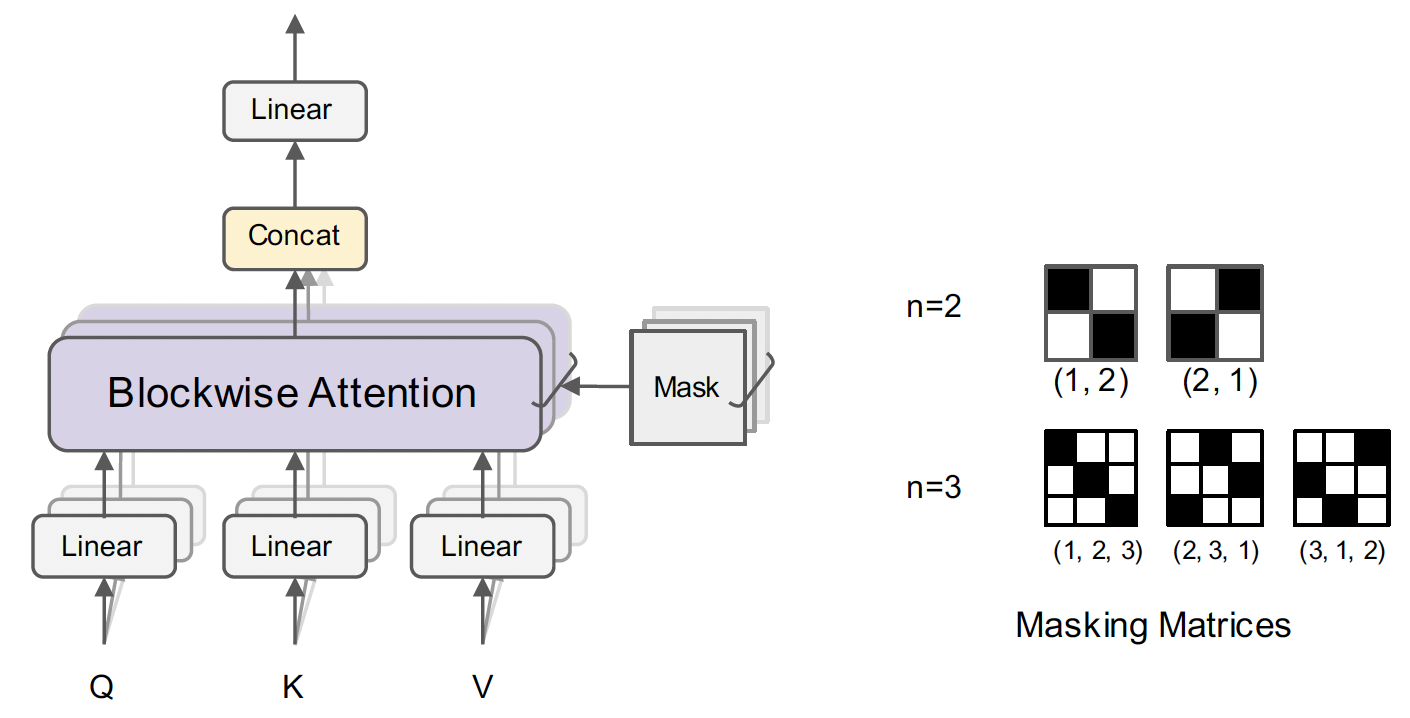

Blockwise Multi-head Attention [8]

Blockwise Multi-head Attention (Figure 7) introduces a sparse block masking matrix $M$ to the $N\times N$ attention matrix. Each masking matrix is determined by a permutation $\pi = \{1,2,...,n\}$. Blockwise sparsity captures both local and long-distance dependencies in a memory efficiency way, which is crucial for long-document understanding tasks. The sparse block matrix $M$ is defined by

$$ M_{ij} = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } \pi(\lfloor\frac{(i-1)n}{N} + 1\rfloor) = \lfloor\frac{(j-1)n}{N} + 1\rfloor, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} $$Energy Transformer with Hopfield [9]

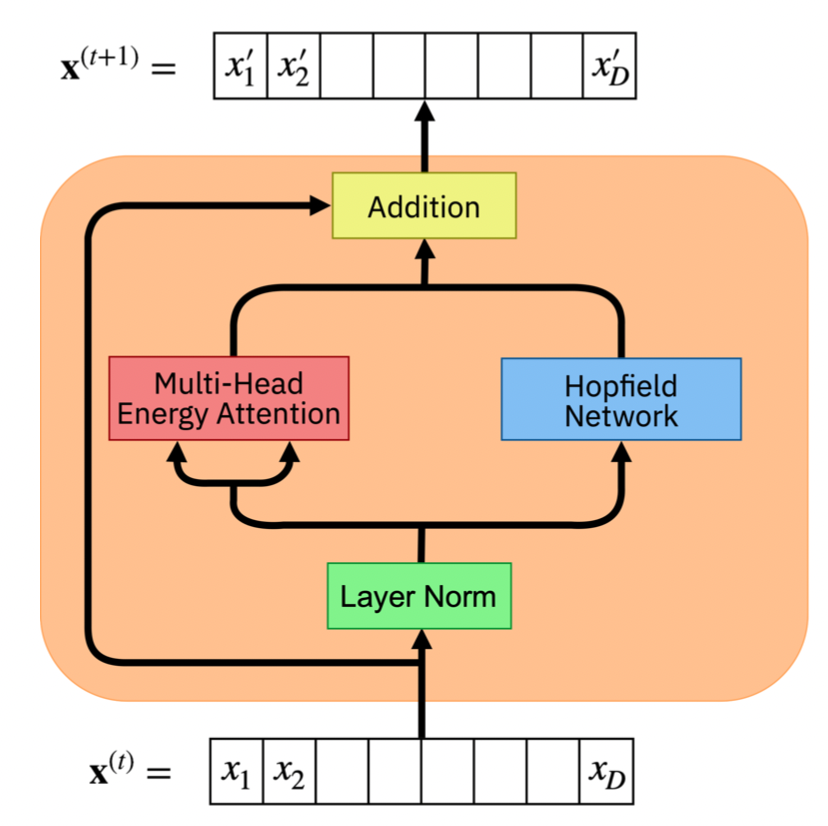

In a Transformer block, there are four fundamental operations: attention, feed-forward multi-layer perceptron (MLP), residual connection, and layer normalization. Energy Transformer (ET) replaces the sequence of feed forward transformer blocks with a single recurrent Associative Memory model. The ET block consists of both a Multi-Head Attention module and a Hopfield Network module for attention (Figure 8).

In particular, the energy of the Multi-Head Attention module has shown a resemblance to Hopfield networks in recent studies [10], which is defined as: $$E^{\text{ATT}}=-\frac{1}{\beta}\underset{h}{\sum}\underset{C}{\sum}\text{log}(\underset{B\neq C}{\sum}\text{exp}(\beta\underset{\alpha}{\sum}K_{\alpha h B}Q_{\alpha h C})),$$

$$K_{\alpha h B}=\underset{j}{\sum}W_{\alpha h j}^K g_{j B},$$ $$Q_{\alpha h C}=\underset{j}{\sum}W_{\alpha h j}^Q g_{j C},$$ where $\alpha$ denotes elements of the internal space, $h$ denotes different heads of this operation, $g$ denotes the output of the layer norm, $j$ denotes the token vector’s element index, and $A, B, C = 1...N$ are used to enumerate the patches and their corresponding tokens.The energy of the Hopfield Network module is defined as: $$E^{\text{HN}}=-\frac{1}{2}\underset{B,\mu}{\sum}r(\underset{j}{\sum}\xi_{\mu j}g_{j B})^2,$$ where $\xi_{\mu j}$ is a set of learnable weights (memories in the Hopfield Network), and $r(\cdot)$ is an activation function. It is a classical continuous Hopfield if the activation function grows slowly (e.g., ReLU), or a modern continuous Hopfield Network if the activation function is sharply peaked around the memories (e.g. power or softmax).

ET aims to tackle image reconstruction (Figure 9) where half of these tokens were masked by replacing them with a learnable MASK token. A distinct learnable position encoding vector was added to each token. The ET block then processes all tokens recurrently for $T$ steps. The token representations after $T$ steps are passed to a linear decoder (consisting of a layer norm and an affine transformation). The loss function is the MSE loss on the occluded patches. ET operates akin to a global workspace, drawing patches towards the global minimum within the system.